The ancient art and science of bonsai teaches more than just patience

When Ron Skibbens decided to build a camp in New Brunswick some 25 years ago, he wasn’t expecting it to lead to a lifelong passion for bonsai.

“We did this hippie thing, you know, building a camp with a chainsaw,” he recalls while sitting in the sunny kitchen of his North End Halifax home in a hibiscus-print shirt. “We literally went down to the woods, cut down 30 cedar trees, hauled them up and built a camp.”

It was one of those 30 trees that provided Skibbens’ entrance into the world of bonsai. He noticed a

small cedar growing out of the

stump of one of the trees. Skibbens knew little about bonsai, but he was intrigued by the cedar sapling.

He says, “I just drove a shovel in at the base of the rotted stump, lifted the whole thing out, stuck it in a bag to bring it back to Halifax, put it in a pot and tried to keep it alive.”

Mission accomplished. That cedar now stands about a metre high in a clay pot on Skibbens’ deck—one of dozens of bonsai he has shaped and nurtured over the years. “That’s a 24-year-old tree, and in the wild it would be 30, 40, 60 feet tall,” he says.

Bonsai—the art of cultivating and shaping trees in containers—took root in China nearly 1,500 years ago. But it expanded and flourished in Japan, spreading to the West in the late 1800s, with a resurgence of interest in the 1980s, after the release of The Karate Kid movies.

While you can buy fully-shaped bonsai at supermarkets and big box stores, much of the pleasure of the art is in taking young trees (or raw material) and styling them over time.

“I consider bonsai a verb,” says Jayme Melrose, co-owner of Props Floral Design in Halifax. While the shop occasionally sells pre-shaped trees, Melrose says she prefers selling “bonsai-able” plants, including “really cute little junipers that are fantastic for bonsai. They have that classic Japanese-style shape.”

With little formal training, Skibbens, who started the Halifax Bonsai Club Facebook page, compares himself to a “folkie” who picked up a guitar, wondered if he could play and sing, and eventually got pretty good at it. “I like the notion of manipulating a tree in a way that makes it hopefully more attractive, more interesting. It’s not control as much as it’s positive manipulation.”

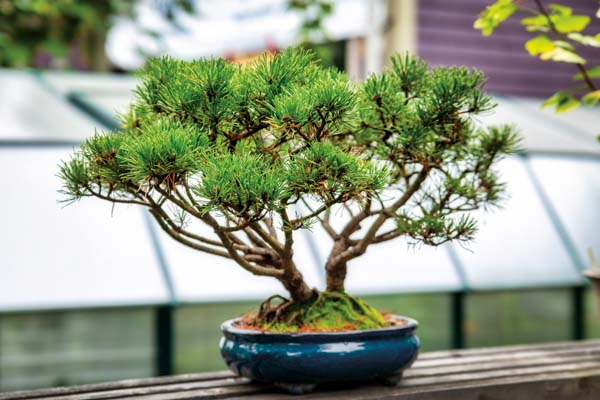

One of his elegant pine trees.

Like Skibbens, Grant Chisholm of Halifax also started out by digging up plants. (The bonsai term for trees collected in the wild is yamadori.) Chisholm, a 30-year-old craft brewery employee, became interested in bonsai as a pandemic project. After he failed to successfully sprout seeds from a kit, he started looking at the plants in his own backyard and in the woods near his mother’s house.

He bought a Japanese juniper (Juniperus procumbens) on Facebook marketplace and “fell in love with keeping this little guy alive.” Chisholm has since added white pines and white oaks dug out of the ground. For now, he’s just watching them “to see which way they want to grow” before starting to shape them.

Many classic bonsai species, like Japanese maple (Acer palmatum) are not native to Atlantic Canada. But there are beginner-friendly native species. Bjorn Bjornholm became fascinated with bonsai after watching The Karate Kid as a teen in Knoxville, TN, and went on to apprentice for six years in Japan. Now, he owns the Eisei-En bonsai nursery near Nashville, which he founded in 2018.

He suggests Eastern white cedar (Thuja occidentalis, whose range just pokes into the Maritimes) and red spruce (Picea rubens). “It’s an excellent species, because the foliage is very small, which makes it very easy... to create a nice, padded look.”

When it comes to buying bonsai, Bjornholm recommends coniferous species like junipers, because they are easy to find and work with. “Look for trees that have a pretty wide-spreading base to them, interesting trunk movement and taper. The branches are the last thing to worry about, particularly when you’re dealing with conifers like junipers where you can manipulate and wire the branches into place.”

Skibbens delights in growing traditional species. He has maples, apple trees, chestnuts, ficuses, lindens, beeches and more. But he is also a big fan of Schefflera, or umbrella plant, as a beginner bonsai. It’s often an office plant that needs little natural light. “You can’t over-water it, you can’t underwater it,” and it takes surprisingly well to life in a small pot.

While there is an essentially unnatural element to miniaturizing and containerizing trees, one of the keys to bonsai is creating a natural-looking environment and bringing out the inherent beauty of the trees. So it’s a good idea spend some time with the trees before breaking out the clippers.

“You want your bonsai to have a front,” Skibbens says. He suggests turning the tree often to determine “the view you want to see most often, so you start planning your style around the front of the tree.”

Getting started with bonsai can seem intimidating. Some teachers have very strong opinions, and some bonsai books can be very rigid in their pronouncements. Unless you’re looking to start winning awards at bonsai shows, don’t get too hung up on the rules.

Bjornholm says many teachers who have spent time in Japan offer good advice in online videos, through sites like Bonsai Empire and his own Bonsai-U. And while trees can (ideally), live for decades or even centuries, Bjornholm says it’s never too late to get into bonsai. With the right species, you can see results fairly quickly.

At his own nursery, Bjornholm has trees he’s thinking about on a timeline of 20 to 40 years. But he says beginners can easily see results much sooner. “You can work with something like juniper and transform that tree from raw material to pretty well-developed in three to five years. It can be a very quick turnaround.” For deciduous trees, think more like 10 to 15 years.

Melrose, who says she dug her first bonsai out of the woods in BC about 20 years ago, says “yes and no,” when asked if she hesitates to recommend people take up the practice. “Frankly, bonsai are high maintenance... They are old creatures in tiny pots, so they need a lot of water. That is mostly how I have killed my bonsai.”

And while the fascination with bonsai lies largely in trimming and shaping, Bjornholm says the art has to be underpinned by a solid understanding of what trees need to thrive. “At least 60 or 70 percent is horticultural and maybe 30 or 40 percent aesthetic or artistic. But quite often the art itself kind of emerges over a number of years as you apply basic horticultural techniques,” he says.

Because beginners invariably make mistakes, Bjornholm suggests not spending a lot of money on a first bonsai. And he says to resist the temptation to go wild and start styling a ton of trees. “Pick out a couple of species that you find interesting, and work with those for a year or so.”

For Chisholm, what started as something to do in COVID lockdown has turned into a new way of seeing the world. “You’re able to take something and make it into a little piece of art—but it’s living.

“You’ve got to work with what’s there, but have a bit of an imagination,” he says. “It has allowed me to open my eyes more, which is great. This little bonsai adventure is affecting my whole life and outlook.”