An Acadian scallop diver first told me that a giant lobster lived under the mooring block of a marker buoy where the Sissiboo River emptied into Nova Scotia’s St. Mary’s Bay. He said this old crustacean had claws as long as a diver’s forearm. So one day, I went diving to check it out. There was a lobster living under that mooring block and the reports of its huge size weren’t exaggerated. I wasn’t surprised. I’ve spent hundreds of hours diving in St. Mary’s Bay as a photographer, a commercial sea urchin diver, and a scuba instructor and I’ve seen a lot of the amazing life in the bay over the years.

Also known as We’kwayik or Baie Ste. Marie, St. Mary’s Bay is oceanographically part of the Gulf of Maine. It’s home to lobsters, scallops, whales, porpoises, seals, and all manner of fish and marine invertebrates. A line from the western end of Brier Island to Mavilette in Clare delineates the seaward boundary of the bay, with the open Gulf of Maine lying beyond. On its northern side, almost its entire 60-kilometre length is just a few kilometres from the Bay of Fundy, separated only by the long, narrow Digby Neck peninsula and Long and Brier islands. On the southern side is the Acadian region of Clare.

At 500 square kilometres, it’s only a fraction of the size of Fundy and its tides are less extreme, ranging five to six metres. Deepest near the islands, where its maximum depth reaches 80 metres, the bay gets shallower as you move east, often with a bottom of sand, silt, and gravel (at the head of the bay, large, ecologically rich mudflats are exposed at low tide.)

Nearer the mouth of the bay where rocky shores and cliffs dominate (there are even a few sea caves on the Clare side), a harder bottom prevails with rocky ledges and boulders, which the tides have sculpted smooth. You’ll find broadleaf kelp habitats, where biodiversity is high. These are my favourite places to dive in St. Mary’s Bay.

Years later, while I was getting ready to explore Bear Cove, a shore dive site not far from the community of Meteghan, I remembered that big lobster at the mouth of the Sissiboo River and wondered how he was. Would I see any big lobsters today?

Suited up in scuba gear and carrying my underwater camera, I made my way across slippery rocks and into the calm autumn water of Bear Cove. The water was only 12C, so I was glad to be sealed in my drysuit.

Slack tide. There was no current. The sea was unusually clear as I swam to deeper water. The surface, 10 metres above, looked close enough to touch. A small school of pollock swam lazily above me. Six-metre-tall broad-leaf kelp swayed rhythmically in a faint ocean swell as the late afternoon sunlight fanned through the canopy of vegetation. A harbour seal or perhaps a porpoise splashed past at the limit of visibility beyond the kelp.

The ocean floor was a patchwork of smooth, tide-sculpted rock reefs and boulders, intermingled with fingers of bright sand. Ripples on the water’s surface refracted light, dancing with soft radiance on the sea floor. You’ll find such kelp beds along rocky shores where boulders and ledges provide a secure place for the plants to attach. Calling such a place beautiful doesn’t do it justice. Magical is closer to the mark.

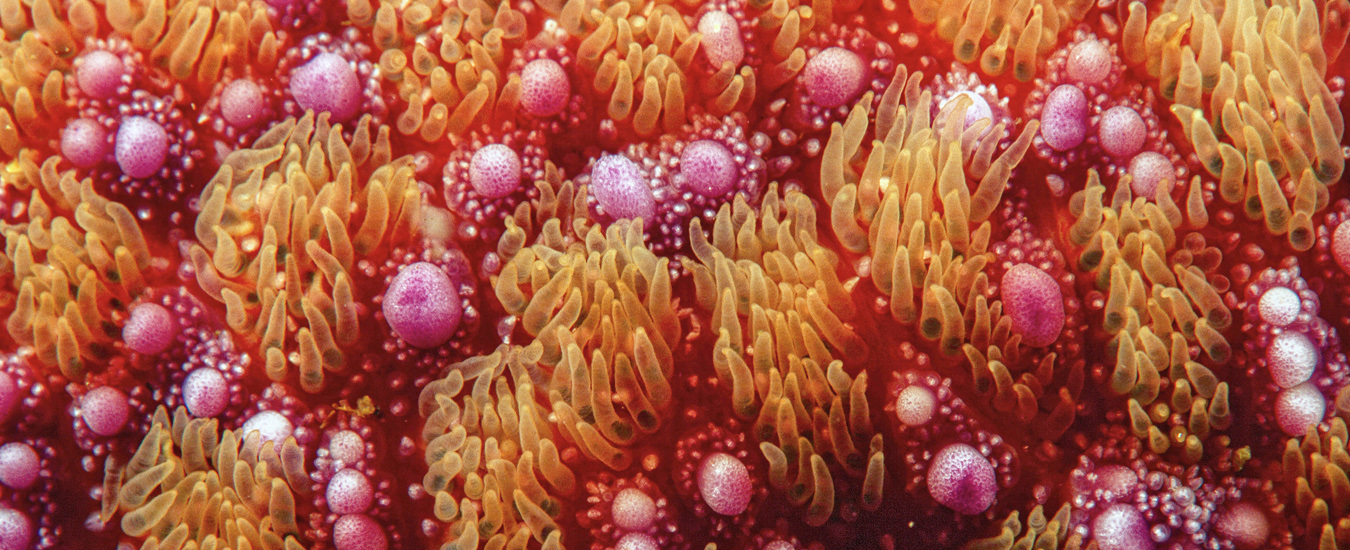

The kelp ecosystem’s diversity stems from the abundant surfaces on which a variety of animals and smaller plants live. Hundreds of small, stationary invertebrate animals known as bryozoans (a primitive lace-like organism) and hydroids (small jellyfish-like polyps) were on every kelp frond. Dozens of species of worms, molluscs, and crustaceans wandered over the stems and holdfasts (the claw-like base of the plant that grips the rocks) of the kelp. And most beautifully, northern red anemones like big succulent flowers lived on the vertical sides of fissures in the rock ledges. Myriad other strange animals, such as fan worms, nudibranchs, sponges, and sea peaches clung to the kelp or rock, creating a tapestry of bright colours under my camera flashes.

At the bottom, I disturbed a large lumpfish tending its eggs. The bright red, blunt-headed fish rose from within a bunch of kelp stems and swam in small circles over its precious patch of roe. Propelling itself through the water by gingerly fluttering its pectoral fins and small tail, it moved slowly and deliberately over the bottom, a Tai Chi master of the sea.

Nearby on a large patch of sand between the boulders, hermit crabs ignored my looming shadow and the din of my bubbles. They seemed to populate every square metre of sand, scuttling away in every direction to make way for a large lobster that lumbered towards me across the bottom. And, true to the optical physics of diving, where things viewed under water look 25 per cent bigger and closer than they do topside, it looked like a big one. Still, it was no match for the giant I’d seen all those years ago, but a fitting view to end my brief exploration of St. Mary’s Bay.