God damn them all, I was told

We’d cruise the seas for American gold

We’d fire no guns, shed no tears

Now I’m a broken man on a Halifax pier

The last of Barrett’s privateers

So goes Stan Rogers’ sea shanty, “Barrett’s Privateers,” set in 1778, spinning the fictional tale of the doomed ship Antelope. East Coast pub goers have sung along with the chorus to the sloshing of beer since Rogers wrote and recorded it half a century ago. But how many of those midnight revellers have wondered, what is a privateer, anyway?

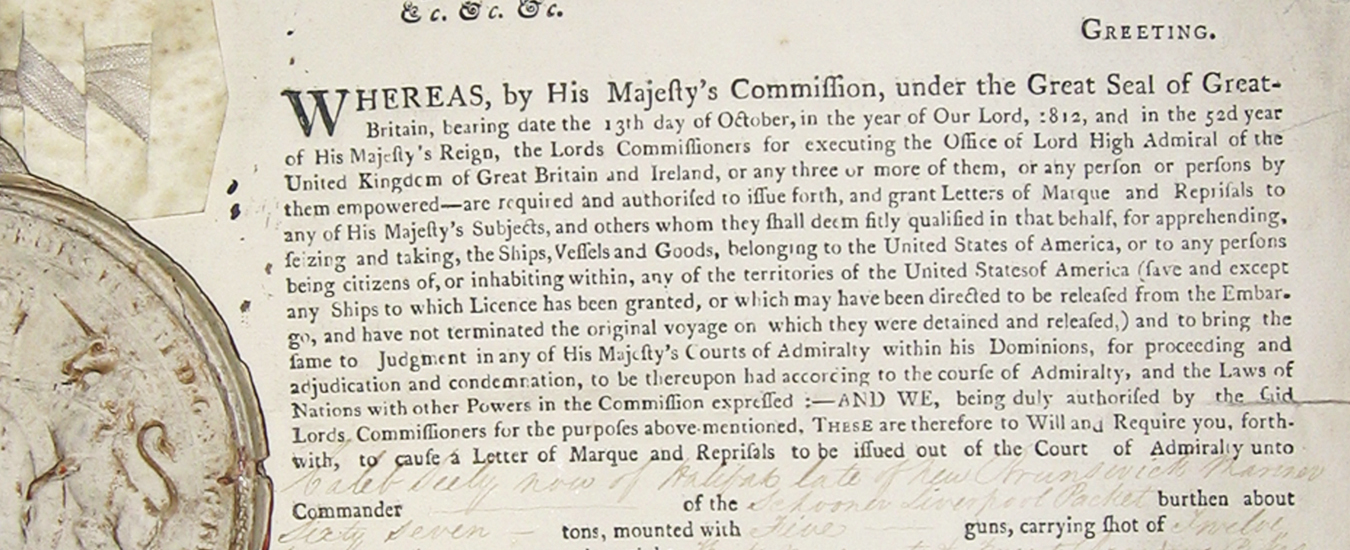

Starting in the 16th century, Britain (and other countries) legalized the seizing of enemy ships by private citizens, or privateers. By providing merchant ships with legal paperwork called a “letter of marque,” Britain effectively expanded its naval forces with merchant vessels armed with weapons and fighting crews. Privateers worked for the profit that came with the capture and sale of enemy ships and their cargo. Because of Nova Scotia’s strategic location, good ports, experienced seamen, and British naval presence, it became a centre of privateering.

“For our little town, it all started when things were getting hard economically,” says Linda Rafuse, temporary manager at the Queens County Museum in Liverpool, N.S. After independence in 1776, America legalized its own privateers, which captured merchant ships in Nova Scotian waters, sometimes nabbing them from Liverpool’s wharves.

“Simeon Perkins recorded in his diary, ‘I don’t know how much longer I can feed my family,’” says Rafuse of the resulting economic hardship. “These were merchants dependent on West Indies trade.” She adds American privateering drove merchants like Perkins to petition the British colonial government for letters of marque so they could fight back.

At the Perkins House Museum in Liverpool, visitors can stand on a replica of the Liverpool Packet privateer ship and fire a cannon at an approaching target. Perkins led the defence of Liverpool against American attack and funded privateers like the Packet. To this day, Liverpool is known as the Port of the Privateers and hosts the annual Privateer Days Festival in late June and early July.

Skillfully captained by Joseph Barss and one of the most effective privateer crews in history, the Liverpool Packet quickly earned legendary status, capturing 33 American ships in a year.

In 1813, the Americans returned the favour, capturing Barss and imprisoning him in New Hampshire. They paroled him, then captured him again a year later in command of a merchant vessel. Upon release, he retired to a quiet life of farming in the Annapolis Valley.

Peter Barss, the privateersman’s great, great, great grandson, grew up in the U.S., but his family visited Nova Scotia often. In 1972, Peter immigrated to Canada and lives in West Dublin, Lunenburg County, and is a photographer and environmentalist. “Captain Joseph Barss has been part of the family lore for many years,” says Peter. “He was presumably the most fearsome privateer during the War of 1812 and practically shut down some ports along the New England coast.”

In 2020, after a long search, Peter found the gravesite of his heroic ancestor in Oak Grove cemetery in Kentville, N.S. “It’s a very simple gravestone, and it doesn’t mention his infamy,” says Barss, “but when I stood there, it was much more emotional than I had anticipated.”

Like the young sailor in the Stan Rogers song, Captain Joseph Barss sought adventure and riches while defending his Maritime home against American aggression. And like that sailor who was promised he’d fire no guns and shed no tears, Barss discovered that privateering was dangerous, deadly work. It’s no wonder he chose to leave the sea behind.

The Crown’s message in those letters of marque was misleading, says Linda Rafuse. “We’re giving you permission to disrupt enemy shipping, but we would prefer no bloodshed. Send the crew ashore because all you’re interested in is the ship and cargo. But of course, we know what happened.” While Captain Joseph Barss was known for his fair treatment of prisoners, battles often raged and casualties mounted, as Stan Rogers immortalized with his visceral imagery.

Our cracked four-pounders made an awful din

But with one fat ball, the Yank stove us in…

The Antelope shook and pitched on her side…

Barrett was smashed like a bowl of eggs

And the main truck carried off both me legs

Neighbours at war

Tensions over territorial expansion in North America boiled over into war on June 18, 1812, when the United States declared war on Britain. In response, the British navy imposed a blockade on American shipping. By the time the war ended with the ratification of the Treaty of Ghent on February 17, 1815, each side had captured more than 1,300 merchant vessels and tens of thousands had died, including 10,000 Indigenous people. Although many historians consider the war a draw, to this day Canadians think of it as a victory over American aggression, as the small British colony repelled all incursions by enemy forces.

The famous fictional privateers

Captain Elcid Barrett, the Antelope, and the narrator of the ill-fated privateering expedition in the Stan Rogers song "Barrett's Privateers" are entirely fictional. Not even the town of Sherbrooke existed in 1778. Inspiration for the song came to Stan Rogers in a story by longtime friend Bill Howell. He set the song to music during a session with the folk band Friends of Fiddler’s Green at Sudbury’s Northern Lights Festival in 1976 and recorded it for the album Fogarty’s Cove later that year.

Other privateersmen

- Captain Caleb Seely: After Joseph Barss retired, Seely (or Seeley) captained the Liverpool Packet, capturing another 14 vessels.

- Captain Joseph Freeman: He sailed the Charles Mary Wentworth, one of the first privateering vessels built in British North America, launched from Liverpool in 1798.

- Captain Alexander Godfrey: Simeon Perkins and fellow investors launched The Rover, a 14-gun brig, in 1800. With a crew mostly of fishermen, Captain Godfrey attacked and captured three Spanish ships that same year.