For generations, St. Stephen, NB and Calais, Maine, have been joined at the hip. Will COVID-19 separate them? Not if “The Steve” has anything to say about it

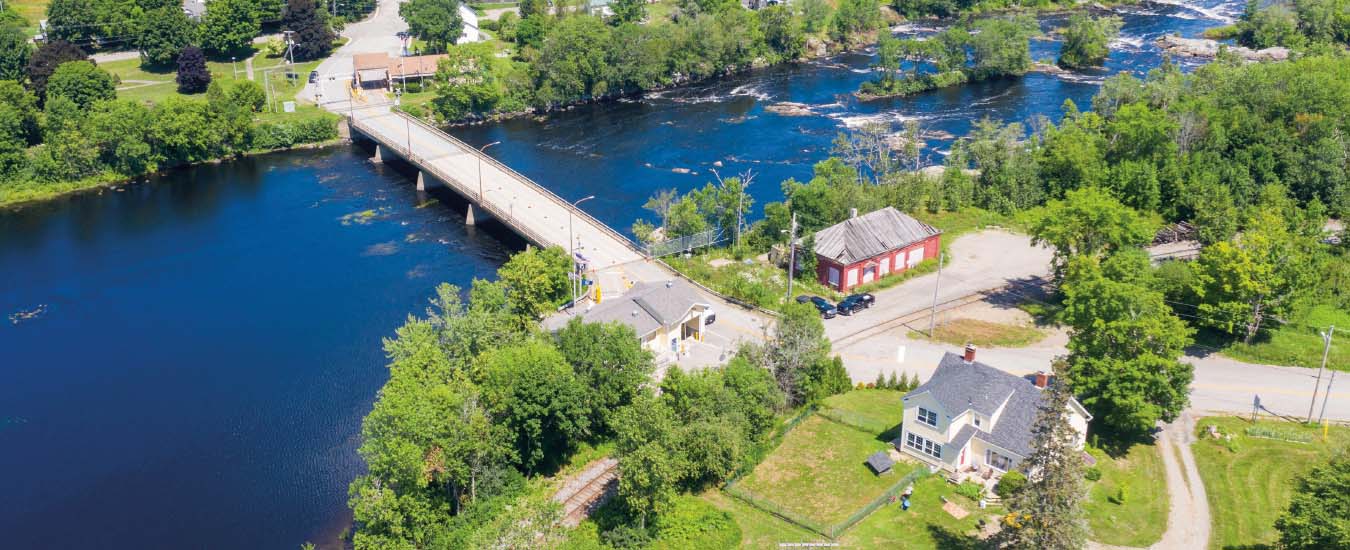

The St. Croix River splits the towns of St. Stephen, New Brunswick and Calais, Maine, like the Judgement of Solomon. But people here don’t much care that a foreign boffin once thought running an international border through their watery main street was a splendid idea. Most here—where New Englanders and Maritimers have mixed and married for hundreds of years—don’t think of themselves as either Canadian or American. They think of themselves as citizens of a place they like to call “The Steve”.

“That’s what the young people say when we try to nail down who we are,” cracks Darren McCabe, St. Stephen’s unofficial historian, whose sister Dawn lives with her American husband across the border. “The Steve is a Canuck and a Yank. He can be frank and opinionated. But when the chips are down, he’s the first to pitch in.”

These days, for The Steve, the chips are down. Way down.

Like everywhere else, COVID-19 has waged a relentless campaign against physical and mental well-being, pushing public institutions to the breaking point. And, like everywhere else, people are impatient, moody and afraid. But, unlike almost everywhere else, The Steve straddles two national realities—two distinct government responses and reactions to the emergency—in one culturally integrated community.

The border that had been nothing more than a suggestion is now, with the lockdowns, an edict and, in a sense, a judgement on the wisdom of forging ties that bind. The question on everyone’s mind now is: Can those ties survive?

“It’s really heartbreaking,” McCabe says. “The Covid thing has really struck a chord. We want to see our towns open again. We want to be able to go freely back and forth again. But we’ve had to put a hard line right down the middle of our community, and people just aren’t used to it. Even after 9/11 [in 2001], when the borders shut down, things were surreal only for a short period. This is a whole different level. This has been going on for more than a year. Even in 1918 [during the Spanish Flu], we didn’t do this.”

It’s almost impossible to overstate the historical closeness between St. Stephen and Calais or, in fact, their overt similarities. Both towns are about the same size—each home to about 3,000 people. Calais is a major shopping centre for both Maine’s Washington County and New Brunswick’s Charlotte County. St. Stephen, home of Ganong chocolates and assorted small businesses, refers to itself on its official website as “The Middle of Everywhere” with “easy connections to major cities, international airports, affordable property and a low-stress lifestyle.”

The first French settlers arrived in the area—the ancestral lands of the Passamaquoddy, an Algonquian-speaking people of the Wabanaki Confederacy who had occupied the territory for thousands of years—in 1604. Two hundred years later, the Americans formally incorporated “Plantation Number 5 PS” as Calais to honour French assistance during their Revolutionary War against the Brits.

Meanwhile, fondness for the English Crown on this side of the border was never as ardent as successive colonial governors repeatedly claimed. According to a 2010 article in the St. Croix Courier, after the Royal Expeditionary Force supplied St. Stephen’s elders with a sizeable cache of gunpowder to defend themselves against the Yanks during the War of 1812, they promptly handed it over to their counterparts in Calais. “Even that conflict didn’t affect this area,” McCade says. “Actually, a peace committee was struck by the area’s churches to work out our differences.”

A young couple originally from the area came to St. Stephen in October 2020 to be married on the wharf, so their American family members could watch across the river. Photo credit Town of St. Stephen

When the Pork and Beans War of 1842 (so-called for the staple food of the area’s lumberjacks conscripted to fight) finally settled the border between Maine and New Brunswick, it went without much comment or notice, probably because no one died in the conflict. As American historian John Robson notes in his blog, “It’s a bit of a letdown for military buffs because there weren’t any battles. Instead, this squabble ended in the Webster-Ashburton Treaty, in which two major powers with a history of belligerence cheerily tossed bits of land at one another and made permanent peace.”

Calais and St. Stephen have been celebrating together ever since. Says McCabe: “We’ve loved our July 1 in Canada. But we’ve also loved our July 4. The first week of that month has been really something. You’ve got this great big celebration between two communities sharing the same experience all at the same time. The parades would start on the Canadian side one year, and on the American side the next. People would march across the border in both directions—go get their beer in Calais and then go to the concert in the park in St. Stephen.”

Indeed, St. Stephen Mayor Allan MacEachern seemed to speak for the entire cross-border community when he took the mic at the annual homecoming festival in August 2017. Gripping Calais Mayor Billy Howard’s hand tightly, he declared: “It is very important to keep this going. I can’t imagine having [your] community on one side and us on the other and not having this connection. It’s always been one big community. I want to keep holding on to that community and keep our friendship strong. We’re stronger together. No matter what goes on in the world we’re always here together—friends, family, businesses, all of us. Let’s keep holding true to that.”

To which a beaming Howard replied: “Well said.”

Certainly, McCabe still has faith. He was born and raised in St. Stephen. After university and a stint in the Canadian military, he returned to become the New Brunswick government’s regional manager, a position he has held for 25 years. He runs the Facebook page, “St. Stephen, In Times Past,” which “offers residents, former residents and friends a place to share cherished memories, photos and interesting tidbits of our collective history and memories.”

He says The Steve is still strong, still kicking, still helping. But, he admits, he worries. COVID-19 has shut down key cross-border services, such as firefighting. It’s wreaked havoc on Calais’s local economy, which depends on Canadians crossing over to eat, drink and buy more cheaply than they can at home. And it doesn’t help that neither the pandemic’s progress nor the American and Canadian responses to it are uniform.

By last June, two months after the emergency began, the Centre for Disease Control in the United States had recorded only two cases of COVID in all of Washington County, and none in Calais. By February, infections in Maine were increasing by as much as 250 per day, with several outbreaks in churches directly across the river from St. Stephen. That prompted Mayor MacEachern, commenting on the first confirmed COVID case in St. Stephen, to tell CBC News: “People are scared [about] a lot of chatter [that it] came from Calais.”

Since then, the pendulum seems to have swung the other way. Last month, official cases in Calais were down as vaccinations galloped ahead of expectations. Meanwhile, access to immunizations have only just picked up in New Brunswick (in fact, across Canada), while infections on this side of the border near St. Stephen have jumped. “Yeah, I learned just now about an exposure a few days ago,” reports McCabe, who keeps his pipeline to the province’s emergency services wide open even while he’s being interviewed for a magazine story. “It came in at the port side of the river. Three confirmed cases. One hundred people are isolating.”

All of which may be, as McCabe says, “really hard” on those health and public safety officials who are duly appointed to battle the spread, but it pales in comparison to the psychic pain of those who’ve been caught on the opposite side of the St. Croix, away from their loved ones. “COVID has split families like nothing else in our history,” McCabe says.

He should know.

In Perry, Maine, about 20 miles southeast of Calais, Dawn Marie Kinney may get the chance to finally hug her husband Terry’s daughter when and if she comes over from England this Christmas. But the St. Stephen native, who’s lived and worked in the US for more than 20 years, hasn’t seen Darren, her younger brother—or her three daughters, one son, and nine grandchildren—in more than a year.

“It used to be every Friday, when we’d go and get the grandkids right on the opposite side of the border and take them to the McDonald’s or Subway in Calais,” she says. “We’d do whatever they wanted to do. If they wanted to stay, they stayed. If they wanted to go home, we’d take them home. It was no big deal. One time my son came down to the wharf on the river with his two boys, and we kind of hollered at them from this side. Okay, that was nice, but that was it. There are a lot of broken families, border families, Canadians who live in the United States.”

Kinney remains optimistic, but she’s also clear-eyed about the immediate future. “We’ve always considered [Calais and St. Stephen] like one community,” she says. “And it is. But it does feels like even when the borders eventually open up, it won’t be the same. There’ll be some distance, right?”

Still, signs are hopeful. Bloomberg News reported last month: “The UK is close to being able to ease most Covid-19 restrictions following a successful vaccination program and a drop in infections, Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab said, suggesting a handful of safeguards will remain by mid-year.”

Meanwhile, the US appears to be turning some kind of corner. “After hovering at stubbornly high levels or increasing over the past two months, average daily cases in Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, Illinois, and other states in the Midwest and Northeast have started to fall, providing a breath of relief that the communities are past their most recent peaks,” a report in the American health technology journal Stat.com stated in April.

“Experts are cautious that the progress has just begun and needs to be sustained if the states want to actually achieve low levels of transmission. But they’re heartened that it appears vaccines are increasingly not just protecting individuals from COVID-19, but are starting to have broader benefits for communities.”

In Canada, the progress may be slow, but at least the expert opinion seems to be aligning. “There is a way to break the pattern, and the way to break the pattern is through mass vaccination,” infectious disease specialist Dr. Isaac Bogoch told CTV in April. “The goal is really to vaccinate as many people as possible over the shortest period of time as possible. And frankly, that will really alleviate a lot of this cycling of lockdown and doubt.”

According to the Government of Canada’s Health Info database, 11 million Canadians, or 30 per cent of the population, had received at least one dose of vaccine by May 1. Almost 50 per cent (244,876 people) have been immunized in New Brunswick.

Numbers like these appeal to public servants all over the world. They tend to confirm the efficacy of science and common sense. But public servants who are also citizens of North American border towns—people like Darren McCabe—also understand something else, which may escape the attention of those not blessed by community ties that truly bind.

“We have a unique experience,” he says. “And you don’t have to go very far out of this area to lose sight of that. People want to pull together here in St. Stephen and Calais and they are very proud of that because it is so historic to this area, so unique compared with how much of the rest of Canada developed. We’re drawn to connect.”

But, isn’t that at least part of the problem?

“Even under COVID circumstances, we’ve put together a pretty good program that respects all the protocols and is safe,” McCabe says. “Of course, we want to be able to travel back and forth again. Of course, we want to treat the border like we always have—but safely, steadily, carefully. We wouldn’t been able to do that if we weren’t so close, so committed to each other’s well-being.”

Just ask The Steve. After all, when the chips are down, who else can you trust?