By all means, come visit Victoria-by-the-Sea. Just don’t call it a resort town if you know what’s good for you

When you’re in Victoria-by-the-Sea, PEI, you will stroll past the sweetly pretty lighthouse to arrive at the community playhouse the New York Times once called a “hidden gem” and where, possibly, a matinee performance of On Golden Pond is running.

Maybe later, you’ll rent a kayak or dig some clams at Tyron Shoal before heading over to the big wharf at the water’s edge to settle in for a salty snap of serenity watching the sun dip over the Northumberland Strait.

But, when you’re in Victoria-by-the-Sea—with a permanent population of about 76, nestled nicely between Charlottetown and a bridge to everywhere but there—what you won’t do is say this: “Oh heavens, what a nice resort town this is.”

Not out loud. Not if you know what’s good for you.

“OMG, that’s a no-no,” Ron Coffin, the town’s former Chief Administrative Officer, gasped when I make the classic blunder he’s heard from off-Islanders more times than he can count. “The people here consider themselves a residential-artistic-cultural community. They are proud of their history.”

They should be. There’s a lot of it.

Photo: John Sylvester

Established in 1819, halfway between Charlottetown and Summerside, by James Bardin Palmer, a lawyer and agent for John Fane, the 11th Earl of Westmoreland, Victoria’s protected location and calm waters was a godsend to its early mercantile interests. According to the town’s records: “Palmer’s son Donald, following a well-conceived plan, laid out the village on [the family’s] estate. The effect can still be seen today by the grid pattern of its streets.”

By the late 19th century, Victoria prospered with three wharves and many more thriving commercial enterprises doing brisk trade with Europe, the West Indies and ports along the northeast coast of North America. In fact, says the archive, “A wide variety of produce, including potatoes and eggs, was shipped by schooner from Victoria until the early 1900s. In the days of the steamboats, Victoria was a regular stop for the Harland, dropping off visitors from Charlottetown and places further afield to spend a few days relaxing in the beautiful village by the sea.”

Hence the name: Victoria-by-the-Sea. To a degree, the history of the community since then and right up to the present day has been a phased withdrawal from the bustling world that forged it. First came the Trans-Canada Highway, which prompted some businesses and families to relocate to nearby Crapaud, more directly on the way to Charlottetown. Then came the Confederation Bridge, which continued the trend.

In 1982, journalist Stephen Kimber, writing in Atlantic Insight Magazine, observed, “The Trans-Canada Highway bypassed Victoria. So did the shopping centres and tourist amusement parks. And that—along with its independent-minded citizens—is what makes Victoria the enchanting, picture postcard place it is today.” The town seems to like that summary. “Not much has changed in the intervening years,” it states on its website. “You are invited to come and see for yourself.”

And people do, indeed, “come and see.” This past summer, during the first full tourism season of the COVID-19 era, when travel and hospitality operators were gnashing their teeth and wringing their hands over the future of their towns, businesses and entire industry, Victoria plugged along quite nicely, thank you very much.

The SS Harland made regular trips from Charlottetown to Victoria between1908 and 1935, delivering supplies for the stores and taking on produce and passengers.

In July, the CBC reported, “A seaside village in Prince Edward Island is reaping the benefits of business this season, despite a dip in tourism across the Island. Victoria-by-the-Sea, a small seaside community located between Charlottetown and Summerside, is seeing a high volume of visitors and off-Island tourists this summer.”

At the time, some thought the province’s tourism trade would drop by as much as a third, compared with 2019. Not so in Victoria, where new restaurants opened up and local retailers, like Terri Williams of Tidewater Merchants, sang the praises of foot traffic in an otherwise dangerous time. “People come here because it’s quiet,” she told the public broadcaster. “I think all those things just contribute to people wanting to escape to this beautiful village.”

Indeed, said mayor Ian Dennison, “We did reasonably well despite COVID. As a community, we managed to stay vibrant. It just seemed like a very busy season once the Atlantic bubble was announced. We hosted a shortwave radio event at the lighthouse. Even at the playhouse—where the season got cancelled—they staged a production in the fall and did significant renovations through the summer.”

Even so, the community remained vigilant about its reputation, especially about that dreaded word: resort. “It’s funny, but at the beginning of March when the whole COVID thing happened, and everybody was making dire predictions about what the summer would be like with nobody travelling, there was a lot of concern here,” Dennison said. “Then, all of a sudden, when people from Atlantic Canada were travelling here and we were seeing tourists, the concern for a number of residents turned to, ‘Oh my gosh, there are so many people in the community; where are they going to park?’”

To someone from away, the concern seems odd. After all, there’s almost nothing about the village that isn’t, well, at least somewhat resort-like. In addition to the lighthouse, playhouse, sea kayaking and clam digging, there’s the Landmark Oyster House, the Lobster Barn Pub and Eatery, Beachcombers on the Wharf, and Island Chocolates all within five square kilometres of each other. (You find that kind of tourism density in places like Rio and Orlando).

Moreover, a visitor has always had his pick of places to hang his hat: From the Victoria Garden Suite and Victoria Cottages, to the Orient Hotel and the Grand Victorian. He also has his heart contented with all manner of artisanal products: From soaps, fabrics, and jewelry, to pottery, antiques, and crafts. At one time, he could even pop by PEI’s biggest tree, a 102-foot American Elm with a 129-foot canopy.

Courtesy of Halibut PEI. Halibut PEI is a closed-contained, Ocean Wise certified halibut aquaculture operation.

Victoria may be a fully incorporated municipality under provincial jurisdiction, but as PEI’s third-smallest population centre, it just feels like a place whose main preoccupation should be the amount of sugar in the ice tea it serves visitors. (To be fair, you could say that about a lot of places on the Island, whose entire population could fit into the Greater Moncton area with room to spare).

None of which should dilute consideration of the town’s other sources of prosperity. There’s Halibut PEI (HPEI) which describes itself as “a land-based, closed contained Ocean Wise certified halibut aquaculture operation [whose] broodstock, egg fertilization, hatchery, nursery and grow-out operations make us North America’s only fully integrated halibut company.” Apparently endowed with “geothermal modified salt water wells, HPEI leads the development of an industry in strategic locations across Prince Edward Island, where these wells exist…HPEI’s hatchery facility is capable of supplying grow-outs with 250,000 fish for growth to 3-kg market size fish. This represents enough feed stock for an industry up to 500 tonnes per year of halibut.”

Not far from it is the Center for Aquaculture Technologies, which calls itself “a leader in aquaculture research and solutions…a full-service organization that integrates and customizes services…as the largest aquaculture contract research organization in the world with certification [that] allows [it] to conduct in vivo and in vitro studies with imported as well as domestic aquatic animal pathogens.” In Victoria, where it operates one of two facilities on the Island, a 46,000 square-foot research farm includes “expansive wet and dry lab space. [There’s] housing for eight aquarium lab spaces and one dry lab with 20 rooms.” All of which puts paid to the notion that Victoria is, despite appearances, small fry. “We have two major business on an industrial scale,” Dennison said with more than a trace of pride.

Apart from this, though, the community’s true sense of identity rests firmly in the creative character of its enterprises. “There are a lot of artists in the village which makes it a destination for people,” Dennison added. “A lot of artisans work from their homes, and they can go into a home that’s also being used as retail space and meet the people who are making the crafts. Victoria works really well for small business, and I think that’s part of the reason why people really like it. The scale is very personal.”

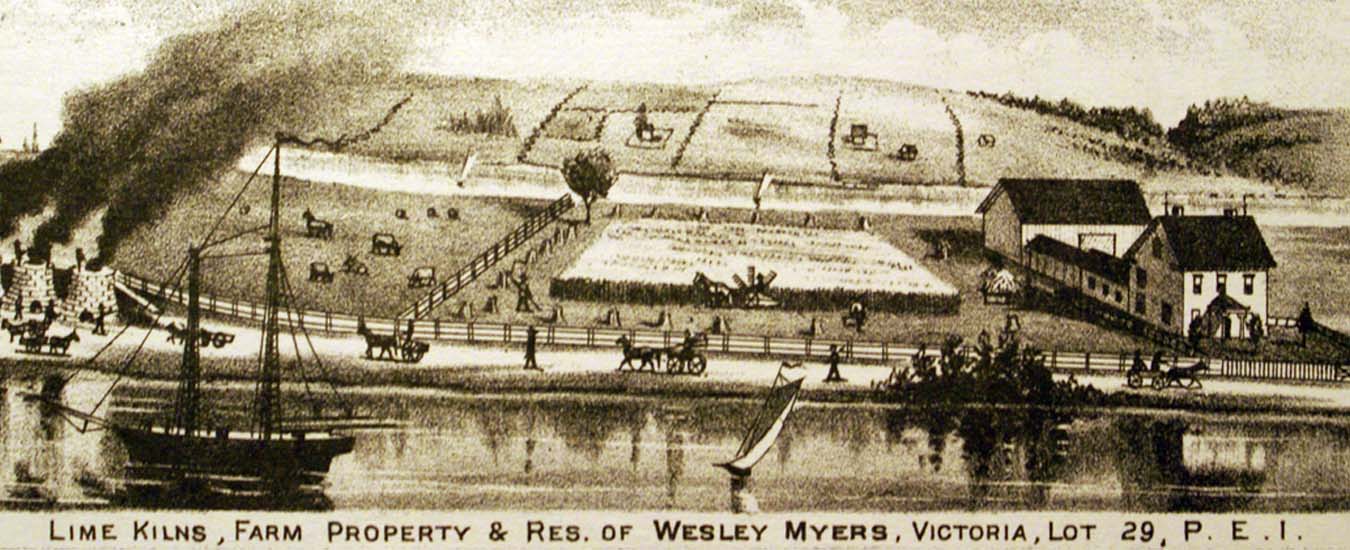

Lime kiln, farm and residence of Wesley Myers at Victoria, from Meacham’s Historical Atlas of PEI, J.H. Meacham & Co, 1880. It is difficult to place this sketch with geographical accuracy today. Descendants still live in Hampton.

It was precisely this scale that Victoria sought to preserve in 2014, when its municipal Council introduced a bylaw that encouraged people to run their hospitality business in situ. At the time, then CAO Hilary Price said, “We didn’t want to provide tourist accommodations from people that have just purchased houses and don’t live here and don’t have a sense of community. We recognize people want to stay here but we wanted to encourage people to use bed and breakfasts and hotels, where people live there as well as providing tourism accommodation.”

Dennison admitted the issue is tricky because the village has a number of seasonal residents. In fact, he explained, “Victoria right now is trying to figure out how best to grow. We are presently working on revising our municipal land use plan. It is a challenge to try to create a plan for land use that will work well into future and keep the community vibrant and oriented towards a good mix of residential, small businesses, fishing, and agriculture, which are all here. It is such a balancing act for a small community like ours.”

That’s a question that members of the community are now weighing as they review the most recent draft of the plan. Said Coffin in October, just days before he finished his term as CAO: “We took it to the community a month ago, and now we are revising it based on the feedback we got. We are really working very hard to make sure that it has the right vision and to make sure that the bylaws support that plan.”

Of course, if you have any acquaintance with the province, you know that the idea someone would leave their homes in one resort…uh, sorry…small community to vacation in a nearby one is only something that could happen here. But, for Coffin, there’s nothing strange about it.

“I actually live near Montague,” he said.

Oh, well, that’s not too far away, I ventured politely.

“Where are you from?” he rejoined, laughingly.

I pull up a Google map and do the math. Oh, I see, it’s a whole 85 kilometres away. So that’s, what? An hour by car?

“Yes, I think it works better if the CAO does not live close to the community where he works. Then, you see, you’re not conflicted by dealing with neighbour on neighbour issues.”

According to Dennison, Coffin finished his term position right on schedule. “He started at the municipality in January,” Dennison said. “He had given us notice. I think he’s heading back to Ontario where he’s from…I mean, like, it’s a super challenge for small communities now.”

Of course, it could be worse. This could be a resort.