Restigouche: The Long Run of the Wild River by Philip Lee

Review by Jim Gourlay

Goose Lane, 272 pp, 22.95 paperback

Conntext is an important word.Canada is blessed with rivers—thousands of them. Their history dates back millennia and significantly predates human development; but in a mere speck of geological time we have outright destroyed or severely damaged many of them and the wildlife that is/was hosted by them.

These catastrophic realities are the result of historically regarding god-given natural resources as either assets to be exploited for monetary gain or private property to be selfishly and exclusively enjoyed by a privileged few.

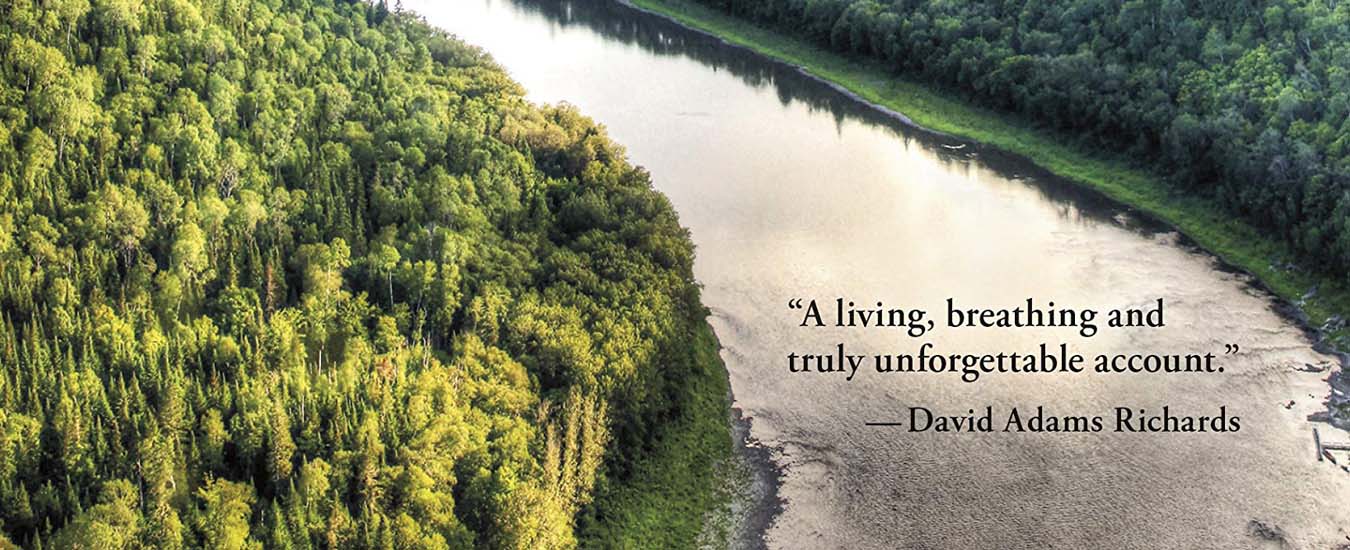

Philip Lee concentrates on only one river system, New Brunswick’s internationally celebrated Restigouche, with which he has a very personal relationship—but the content of this impressively and meticulously researched work exemplifies and summarizes the fate of many systems.

The story outlines in painstaking detail how, through greed, selfishness and mindless, single-focus industrialization, the intrinsic value of this magnificent natural resource was set aside.

“If the river were a hundred years old, it ran free from human interference for its first ninety-nine years. All the major disruptions in the watershed would have come at various times in the last year and the great acceleration of change in the past six months.”

Lee compares the mind-boggling numbers of salmon originally ascending the river with the veritable trickle of fish we have today come to regard as normal and acceptable.

“…Ferguson and Christie captured and exported fifty-five thousand to sixty thousand large salmon every year. Others had taken a great many more than that…How did it happen that the runs of salmon have been reduced to what they are today? Instead of answering that question we lower the bar and declare the salmon runs to be healthy when the river meets the government’s new conservation targets of fifteen thousand spawning fish.”

Lee’s work includes perhaps the most articulate and compelling history of blatant racism and the violation of aboriginal history and basic rights this reviewer has ever read. The detailed comparison between the Indigenous philosophy on their benign relationship with the natural world and the exploitive European influence is stark.

It also touches on the bizarre story of how the British introduced into Canada their selfish feudal system of exclusively reserving natural treasures for the privileged class.

“In the nineteenth century New Brunswick adopted this system of riparian rights on its salmon rivers. The new American aristocrats…bought into the opportunity to buy private fishing rights on the Restigouche, not only because the river offered the finest angling opportunities on the continent but also because these rights were unavailable in their own country.”

Much of a Canadian river could be, and still is, “owned” by non-Canadians, at the expense of Canadians, when foreigners are prevented from doing the same thing in their own country.

The work is extraordinarily well crafted—what is essentially an academic exercise has been transformed into a hard-to-put-down page turner, as compelling as a fine novel. The all-important various contexts in this story (which the author confesses were daunting in their complexity) are clearly explained and skilfully tied up with a bow.

“This region has been a jurisdictional challenge...with administrators from the Canadian Government, two provincial governments, Mi’gmaq nations, private fishing clubs, and municipalities…the river has been managed by a different set of rules depending on whether you anchored your canoe on the New Brunswick or Quebec side of the river…”

The book will obviously appeal particularly well to those afflicted by and addicted to salmon fishing but equally well to amateur historians and the growing number of those among us who care deeply about preserving the abundant natural resources in this vast and sprawling country.

The text is enriched by the author’s hands-on personal anecdotes about his experiences over decades on what is a very user-friendly watercourse for small boats.

Historically, the brutal realities of the vast New Brunswick wilderness for Europeans and early Americans who ventured there without the intrinsic knowledge and skills of Indigenous people is painfully detailed to the extent that the reader cannot fail to admire those who dared to challenge it.

It’s an enlightening, enjoyable read in many ways.