Been there, done that

LATE LAST year, three Maritime senators brought forth an idea that was variously greeted with indifference, resistance and lukewarm praise.

Those gentlemen had raised—once again—the question of whether the three Maritime provinces would be better served by becoming one.

I doubt that they were seriously proposing a political merger; what they were likely attempting to do was kick off a discussion about the many ways the provinces could increase cooperation and realize economies of scale.

But few among the general public know that such unity once did exist—for a brief period in the 18th century. The Treaty of Utrecht in 1713 assigned the region’s mainland to Great Britain, and the islands in the Gulf of St. Lawrence to France.

Fifty years and two wars later, the whole kit and kaboodle became British territory. The only organized government then functioning hereabouts was that of Nova Scotia, so from October 7, 1763, until June 28, 1769, Île St. Jean (now Prince Edward Island) was part of Nova Scotia, although it was never formally represented in the Nova Scotia Assembly.

New Brunswick was included in Nova Scotia until the spring of 1784, and both Sunbury County, NB, (much larger then than it is now) and Sackville Township, NB, elected members. One member for Sackville was Richard John Uniacke, who, years later, became Attorney General of Nova Scotia.

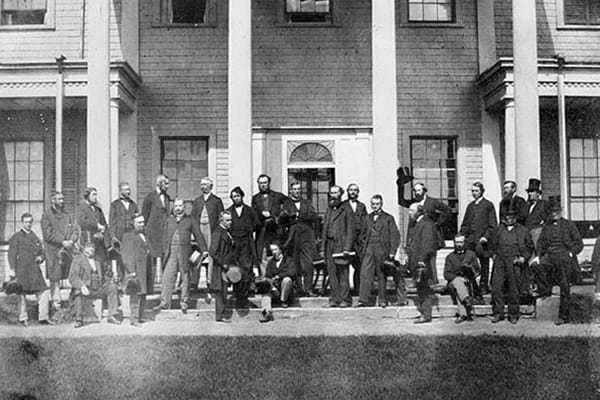

For the next 75 years, the three provinces experienced the growing pains of large-scale immigration and economic development. By the 1860s, conditions seemed favourable for some kind of union among the three, perhaps even to include their distant cousin, the island of Newfoundland. A meeting to discuss the merits of the idea was held in Charlottetown in 1864.

What happened next, in fact, led to the creation of Canada three years later. A persuasive group of Canadian politicians attended the Charlottetown Conference. After several ups and downs, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia joined with Upper and Lower Canada to create the Dominion of Canada. Prince Edward Island adhered six years later, while Newfoundland and Labrador remained outside confederation until 1949.

The genealogical significance becomes apparent in our common heritage between these four provinces. As anyone who has lived in this region for more than a generation or two will discover, among the family tree’s roots or out on one of its limbs, there will be people from more than one of these provinces. Former Nova Scotia premier Robert Stanfield’s family had Prince Edward Island links, as did that of Newfoundland’s Joey Smallwood, to cite two prominent 20th-century examples.

In my case, I live in a house at a T-shaped intersection. People from each of the Atlantic provinces live within six houses up or down these streets. We all look the same, dress the same—and only by knowing one another personally have we discovered that we were born among all four provinces.

Statistics from 2006 showed that one in every 10 people in Atlantic Canada had changed their province of residence within the preceding 10 years. People have followed their career paths, been posted with the armed or civil services, or married from one province to another.

Genealogical sleuths tracing the roots and offshoots of regional family trees can expect to be required to learn at least a little bit about who lived where and when if they are to track down all the twigs and branches.

Most of us have already learned that, at some point in the past, family members went to “the Boston States” or “Upper Canada”—but we sometimes fail to look closer to home for those “missing” cousins and great granduncles and aunts. Even the 1881 census shows that thousands of us had migrated within the region. What’s more, like shifting sands, we are still drifting about the Atlantic region.

We may not have political or even economic unity, but we certainly give the impression of shared roots. With each generation, the more we may talk of being different, the more we are actually becoming the same.

Dr. Terrence M. Punch is a member of the Order of Canada. His latest book, North America’s Maritime Funnel: The Ships that Brought the Irish, 1749-1852, was recently published by Genealogical Publishing Company, Baltimore.