Onshore oil and natural gas development may bring cash to government coffers, but at what cost? Will the quality of life soon be radically altered for thousands of Maritimers?

Jane Bradbrook makes a left-hand turn out of her driveway, pulling leisurely onto Country View Road. Driving slowly, she motions from side to side, pointing out the key sights of “downtown” Corn Hill, NB.

On the left is an 800-acre community pasture where local farmers graze their cattle. Farther along is Joerg Von Waldow’s 500-head dairy farm. And then there’s Corn Hill Nursery, where fruit trees, shrubs and perennials are grown without pesticides or chemical fertilizers.

Corn Hill, a community of a few hundred families, lies in a fertile valley that runs from Sussex to Moncton. On this summer evening the valley is still, with only the odd bird song or distant dog bark punctuating the silence. The valley walls, thickly forested, run down to rolling green farmland, which seems to glow in the early evening light.

“Let’s just stop for a moment on this road,” Bradbrook says, pulling onto the shoulder. “Look around and count the number of cars you see,” she continues, knowing full well there isn’t another car in sight. “This is one of the most beautiful places I have ever been. Now, imagine if we had natural gas wells up and down this valley.”

Like an increasing number of Maritime towns and villages, Corn Hill is situated in an area slated for natural gas exploration. Companies hailing from as far away as Calgary and Texas are now searching for oil, natural gas and coal bed methane across the Maritimes, on enormous tracks of land ranging from Cape Breton to southern New Brunswick and central PEI.

Corn Hill sits within a large parcel of land held under exploration license by Corridor Resources. Through its agreement with the New Brunswick government, the Halifax-based company owns the exclusive right to explore for both oil and natural gas in the area.

Corridor, an independent Eastern Canadian oil and gas company, is currently the Maritime region’s lone producer of onshore natural gas, pumping out 15 to 20 million cubic feet of gas per day from about 30 wells at the McCully Field near Sussex. But Corridor is now exploring a much larger natural gas deposit in a New Brunswick shale formation known as Frederick Brook.

Shale is a fine-grain greyish-black rock, which, in the case of the Frederick Brook deposit, can exceed one kilometre in thickness. In 2009, a third-party study concluded the Frederick Brook shale could hold 67.3 trillion standard cubic feet of gas. For Corridor, the question is this: how much of that gas is actually accessible—and economically speaking—worth drawing out of the ground?

Jane Bradbrook has no desire to find out. Her group, the Corn Hill Area Residents Association, is calling for a ban on shale gas development in New Brunswick, fearing it will bring environmental damage and a huge lifestyle change to Corn Hill and other rural areas.

Her concerns seem justified: according to the National Energy Board, a federal regulator of Canada’s energy industry, shale gas developments pose a number of serious environmental concerns. For instance, impurities in the gas, such as carbon dioxide and hydrogen sulfide, must be vented into the air to prevent the corrosion of pipelines and equipment.

In BC, natural gas production in the Horn River Basin shale is predicted to annually generate 3.3 million metric tonnes of carbon dioxide. That’s equivalent to half the emissions spewed by all of Canada’s pulp and paper mills in 2006.

Hydrogen sulfide, meanwhile, is a flammable gas that often smells like rotten eggs and can cause eye irritation, headaches and breathing troubles in low concentrations.

“Government regulations are not enough”

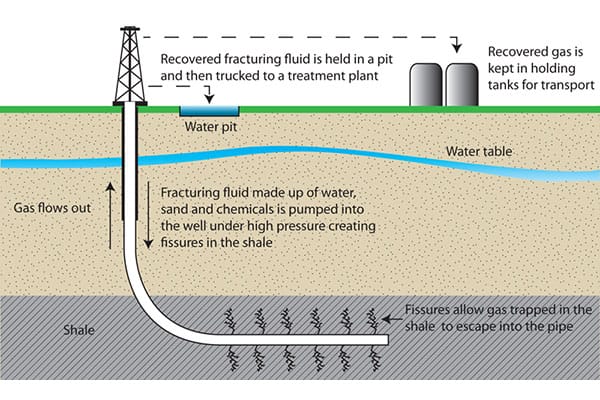

And then there’s the highly contentious issue of hydraulic fracturing. Fracking, as it’s commonly known, involves pumping large amounts of fluid deep into a shale gas well—up to two kilometres below the surface. Under immense pressure, the fracking fluid helps break apart the shale, allowing trapped gas to be released and captured.

Fracking fluid often contains carbon dioxide, nitrogen gas, propane, sand and toxic chemical additives.

The brew also requires a massive amount of fresh water. In the Barnett shale of Texas, for instance, each well requires an estimated 11 million litres of fresh water. And after the fracking is complete, the fluid must be kept out of the surrounding watershed, or carefully disposed of if it returns to the surface.

“Little is known about what the ultimate impact on freshwater resources will be,” noted the National Energy Board in a 2009 primer on Canadian shale gas developments. “It is very early to come to any conclusions about how development of this potentially large resource will impact the environment.”

Such uncertainty leaves Bradbrook worried about the future of Corn Hill. Could natural gas activity leave her farming community with limited or contaminated water? And what about the dust, noise and road damage that would arrive with the army of trucks needed to service the well sites? What of the potential for spills and accidents?

“We truly believe the current government regulations are not enough to protect us,” she says. “We’re fully aware that this government is greatly in debt, and we need to do something. But I don’t believe that the farmers and rural residents of this province need to shoulder the whole burden.

“We’re not prepared to be the sacrifice zone to solve the provincial debt.”

As the crow flies, the community of Penobsquis is roughly 15 kilometres due south of Corn Hill. Located just east of Sussex, Penobsquis is home to a large potash mine, whose four towers dominate the skyline. Nearby is Corridor Resources’ McCully Field gas plant.

Since 2004, nearly 60 Penobsquis families have lost their well water. At first, water was trucked to local homes two or three times a week. By 2009, the province had spent $10 million to set up a new water system, which draws from a well near Fundy National Park. The arrangement makes for an odd sight: in place of water wells, red hydrants now dot farmers’ fields and back country roads in Penobsquis.

The cause of the Penobsquis water disappearance has never been proven. Nevertheless, a number of residents are seeking compensation before the province’s mining commissioner.

Among them is Beth Nixon, a married mother of four who lost her water in fall 2007. Standing on a hay-covered hill on her fourth-generation family farm, Nixon looks toward a gas compressor station that sits just off her property. A constant flame shoots up from a flare stack.

Underneath the field in front of her light blue farmhouse is a natural gas pipeline. Farther down the road, a gas well sits on property her family has leased to Corridor since 2004.

The farm, which now only produces hay, was handed down to Nixon after the recent passing of her elderly parents. She must now decide whether to keep it or sell it. “You want to know you can pass your land on to your kids, like it was passed to you. But what are you going to be passing on?

“Natural gas development is going to industrialize and change rural areas. We need to decide as a society whether that’s what we want. It’s not only an economic decision. It’s a lifestyle decision. It’s a cultural decision.”

Development to date

Penobsquis may represent the epicentre of the Maritime natural gas industry, but it’s certainly not the only area of interest. In all, nine companies in New Brunswick now hold Crown search licenses or leases, which provide the exclusive right to produce oil and natural gas in those areas. New Brunswick’s Crown agreements cover more than 14,000 square kilometres, roughly a fifth of the province.

On PEI, Corridor Resources holds a pair of permits to produce oil and natural gas on land in the centre of the province, while Toronto-based PetroWorth Resources holds four permits for central and eastern PEI. At this point, there are no producing wells on the Gentle Island.

Similarly, there is no current production in Nova Scotia, although seven companies have secured exploration or production agreements with the province. The Nova Scotia government is leasing large land blocks ranging from Windsor to Cape Breton. Three additional land blocks, running from Pictou to Amherst, will soon be assigned. Successful bidders in Nova Scotia secure exclusive exploration rights for a block of land, but they must still seek approval for all activity, from seismic testing to drilling.

Last fall, for instance, PetroWorth Resources applied to drill an exploratory oil well on private property in Cape Breton, less than a kilometre from Lake Ainslie, the largest natural freshwater lake in Nova Scotia. The Department of Environment approved the application on July 29th; at press time PetroWorth was awaiting a green light from the Department of Energy.

Each designated land block contains many exclusion zones, such as designated watersheds, provincial parks and aboriginal land. Individual landowners can also deny access to their property. However, the province—which owns the minerals below the surface—has the power to expropriate land it deems valuable to the public good.

The Nova Scotia government has not yet deployed that power, and it seems unlikely it will have to. Thanks to horizontal drilling technology, natural gas companies can drill up to 10 or more wells from one site (see diagram above). Those tentacles can easily snake for hundreds of metres at horizontal angles under the ground. In other words, a drill set away from a rural home can still access the land (and gas) underneath it.

“The potential is gigantic”

Tom Alexander is an American engineer leading Southwestern Energy’s hunt for natural gas in New Brunswick. When presented with the facts, Maritimers will see that natural gas development can aid the economy without harming the environment, he says at his downtown Moncton office.

A 30-year veteran of the oil and gas business, Alexander has worked in the Gulf of Mexico and in numerous US states. For more than a decade he worked in Southwestern’s marquee development: the Fayetteville shale of Arkansas.

Like resource-laden Newfoundland and Labrador, Arkansas now enjoys a fiscal surplus while most of its federal cousins wallow in deficit territory. “The potential is gigantic. It changes the fiscal landscape forever,” says the North Carolina native, revealing his folksy, southern drawl. “If we find what we’re looking for, there will be mothers and fathers and sons and daughters and grandchildren working on this project. That’s happening in Arkansas today. And we hope it will happen here.”

Last year, SWN Resources, the Canadian subsidiary of Houston-based Southwestern, began a three-year exploration program that would see the company invest nearly $50 million to answer one question: does New Brunswick’s geology contain a major oil or gas deposit? SWN was testing for oil and gas over 2.5 million acres of land—one seventh of the province’s surface. However it recently suspended its operations a few weeks earlier than planned, after its equipment was vandalized.

New Brunswick’s minister of natural resources, Bruce Northrup, says his government remains committed to exploring oil and gas options. “The public has the right to protest... but we certainly don’t condone blockades and we certainly don’t condone stealing property,” he said to CBC New Brunswick, adding that SWN will resume testing in the future. “They will definitely be coming back.”

SWN had originally planned to drill and frack an initial exploration well next year, which Tom Alexander says should not cause concern for New Brunswickers, as long as they get information about the process from “credible, factual resources.” Over his career, Alexander has directly overseen or been responsible for thousands of fracking procedures. “We have had no instances where (our) wells… caused problems with water. None,” he says. But not everyone in Arkansas agrees with Southwestern’s performance. In fact, the company is facing a couple of lawsuits in that state, launched by residents who claim their well water turned gaseous or was contaminated with chemicals through the fracking process.

Alexander acknowledges his industry can be responsible for heavy truck traffic, noise and intense water use. But he insists water contamination is not a byproduct of his work. “It’s our sincere desire that the truth get out,” he says while flipping through a photo album of neat and tidy Arkansas drilling sites. “This can be done well. And it can be done right.”

“We love this area”

Jane Bradbrook steers back into her driveway, completing her evening swing around Corn Hill. A flowerbed at the front of her house explodes in shades of blue, purple, red and yellow; the green valley extends in all directions from her white and red-trimmed farmhouse—all offering a welcoming sight at the end of each workday, capping her 45-minute commute from downtown Moncton.

In the woodland behind the farmhouse, a herd of beef cattle is escaping the evening heat. Bradbrook’s husband, Lawrence Jones, a fourth-generation farmer, sits nearby. This 160-acre farm, once owned by Lawrence’s great-great grandfather, represents his retirement savings. But what value will it hold if this valley is filled with large trucks and natural gas wells?

“All of us who live here—whether we’re fourth generation or a recent arrival—do so because of the rural and pastoral quality of the area,” Bradbrook says as the evening shadows grow longer. “We love this area because of the cleanliness of the air, the land and the water. And the quietness. If industry was to come to our area, all of those things could be lost.”