Industrial fish farming is changing the face of our coastal communities

There's nothing corporate about the view from Stewart Lamont's office.

Perched on the water's edge, the headquarters of the Tangier Lobster Company face on to the aptly named Pleasant Harbour, a patch of water along Nova Scotia’s Eastern Shore, roughly 100 kilometres from Halifax.

Yet Pleasant Harbour provides Lamont with much more than a pretty view. It also yields some of his company’s lobster supply.

Downstairs, workers are busy weighing and packing live lobsters into shipping boxes. This particular order is headed to Korea. Nearby, a pallet of boxes is ready for shipment to Belgium. It’s a Saturday morning but orders must be filled.

Formed in 2010, Tangier Lobster is the latest incarnation of an operation that has spanned four generations. The company can store up to one million pounds of live lobster in its land-based storage facility, which it operates with R.I. Smith Lobster Co.

Those crustaceans, ranging from 1lb “canners” to 10 lb “jumbos”, are then sorted and shipped around the world—year-round.

Traditionally, Lamont has sent about a quarter of his product to the United States. Increasingly, though, he is shipping orders to Asia, particularly China. As their country booms, Chinese importers crave the “best of the West,” Lamont says—and that includes Canadian lobster. With the Asian appetite growing, opportunity looms; but so does an uncertain threat.

Looking along the coast, Lamont can see Shoal Bay, the site of a proposed open-pen salmon farm—one of three farms proposed by Snow Island Salmon, a Canadian subsidiary of Loch Duart Ltd., a Scottish salmon grower. Like a significant number of Eastern Shore residents, Lamont fears open-pen salmon aquaculture

will foul local waters and damage the valuable lobster fishery.

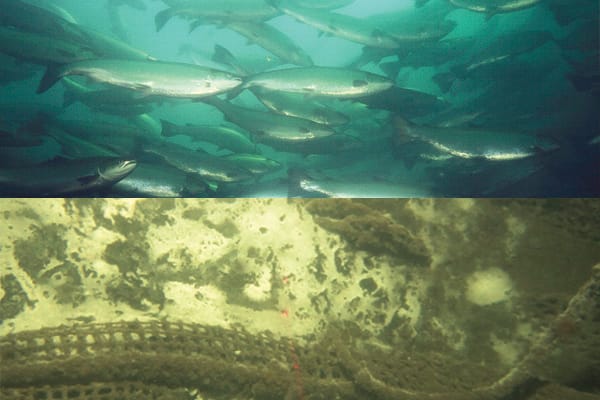

Salmon aquaculture involves raising fish in large net structures close to shore. A single salmon farm, consisting of up to 20 such pens, can hold up to one million fish, although the number of fish farmed on a given site depends on a number of factors, including the site’s area and depth. The industry has existed in Atlantic Canada since the 1970s, with a particularly heavy presence along New Brunswick’s Bay of Fundy coast.

Salmon farming is now poised for a massive expansion in Nova Scotia. In May, the province’s fisheries and aquaculture minister said he wants the local industry to double or triple in value over the coming years.

The region’s biggest salmon farmer, Cooke Aquaculture, is now pushing forward with a $150-million Nova Scotia expansion. Based in Blacks Harbour, NB, Cooke’s Nova Scotia plan includes new fish farms, a new hatchery in Digby, a processing plant in Shelburne and an expansion of its feed mill in Truro. Cooke currently produces more than 160 million lbs of farmed Atlantic salmon per year. The company harvests an average of 200,000 salmon each week from its farms in Canada and Maine.

Lamont admits he knew little about open-pen salmon farming until last February. That’s when he attended a town hall meeting organized by concerned citizens on the Eastern Shore. The event, he says, changed his life.

Since then, he’s read extensively about the industry’s controversial past—one highlighted by disease outbreaks, heavy pesticide and antibiotic use, and massive infestations of sea lice (parasitic crustaceans that feed on the tissue of live salmon).

Of particular concern in Atlantic Canada is the impact of farmed salmon on Nova Scotia’s already endangered wild salmon population. It’s been estimated in the past that up to 2 million farmed salmon escape from their pens each year in the North Atlantic, although the Aquaculture Association of Nova Scotia says they don’t currently track escaped salmon, and are not aware of any salmon escapes from farms in Nova Scotia since the late 1990s. According to one scientific study, interbreeding between escaped salmon and wild salmon from New Brunswick’s Magaguadavic River is altering the genetic integrity of the wild population—possibly reducing their ability to adapt to wild conditions (see also sidebar on wild salmon).

For Lamont, it all makes for troubling reading. As Tangier Lobster’s managing director, he doesn’t secure orders by promising the lowest price. His customers pay a little more for “premium quality.”

“Our lobsters come from a pristine location where there’s no industrial tarnish or environmental concerns,” he says. “We like to have our customers sit in our gazebo and eat a lobster lunch by the water. They can watch the boats fish literally 200 feet off our shore.”

Lamont sources his lobster from waters ranging from Newfoundland to Maine, including Pleasant Harbour. He also draws water from the harbour to fill his holding tanks. In other words, any fouling of the surrounding area would be “devastating” to his business. Even the perception of an environmental stain could scare away customers, he argues. And then there’s the risk of outright destruction, something Lamont is already familiar with.

In 1996, roughly 60,000 lobsters mysteriously died in a holding pound in Back Bay, NB. Four lobster suppliers, including Lamont’s company, owned the crustaceans, which were valued at $700,000. Traces of cypermethrin, an illegal pesticide used to fight sea lice, were later detected in samples of the dead lobsters. The four companies sued several local salmon pen operators for damages. The matter was settled out of court, with the salmon growers paying a “substantial settlement”, Lamont says.

More recently, 19 charges have been laid against Kelly Cove Salmon (a division of Cooke Aquaculture) and three senior Cooke officials (including CEO Glenn Cooke) over a separate incident. Environment Canada alleges the company released a cypermethrin-based pesticide into New Brunswick waters between November 2009 and November 2010. The charges stem from two investigations, both of which examined the cause of dead and dying lobsters. Cypermethrin, which is not authorized for marine use in Canada, is harmful to crustaceans.

The mass lobster poisonings, combined with his recent research, has convinced Lamont that open-pen aquaculture is simply too risky. He’s now a member of the Association for the Preservation of the Eastern Shore, which has joined more than 100 organizations and businesses in calling for a moratorium on further open-pen salmon aquaculture in Nova Scotia. The industry, they argue, should cease its expansion until an independent scientific and economic analysis is completed.

“Is the open-pen business model compatible with the community? Is it compatible with wild fisheries activity? What are the risks?” Lamont asks rhetorically, while lightly banging his hands on his desk for emphasis. “The more you learn about it, the more your level of concern grows.”

Ask any opponent of open-pen salmon farming to explain their case and the conversation invariably arrives at the same place: Chile. In 2007, that country’s aquaculture industry was ravaged by an outbreak of infectious salmon anemia (ISA). Though (reported to be) harmless to humans, the disease kills fish.

The Chilean outbreak spread quickly, killing millions of farm-raised Atlantic salmon, generating billions in losses and erasing 26,000 jobs. And despite efforts to contain it, the virus continues to spread.

In a 2011 editorial, the New York Times called the Chilean aquaculture industry “unsustainable” and blasted the sector for its poor practices, which included raising salmon in overcrowded pens “in the midst of their own pollution.”

“Salmon farming everywhere has repeated too many of the mistakes of industrial farming—including the shrinking of genetic diversity, a disregard for conservation, and the global spread of intensive farming methods before their consequences are completely understood,” the editorial stated. “The death of millions of farmed salmon in Chilean waters was a warning sign that must be heeded.”

First diagnosed in 1984, ISA has spread far beyond the world’s two largest aquaculture hubs: Chile and Norway. Earlier this year, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency ordered Cooke Aquaculture to destroy the salmon at one of its Nova Scotia fish farms near Shelburne, after fish tested positive for ISA. Subsequently, a further two outbreaks of ISA have been discovered, at a second Cooke site in Nova Scotia and another in Newfoundland with a different operator.

The region’s conflicted relationship with open-pen aquaculture is most obviously seen in the experience of New Brunswick, where open-pen salmon farming first emerged in 1978 with an initial crop of 3,500 smolts.

Dr. David Wildish, a marine biologist, tracked New Brunswick’s aquaculture industry from its emergence up until his retirement from the Department of Fisheries and Oceans in 2005. In the early years, he co-chaired a federal-provincial committee aimed at ensuring the sector was set up in a sustainable way. That effort failed, he concludes.

It’s a rainy morning and Wildish is sitting in his office at the St. Andrews Biological Station. Though retired, he still works part-time at the Bay of Fundy research site, holding the title of Scientist Emeritus.

He recalls the industry’s early days, when the provincial government envisioned a new sector to replace the vanishing ground fishery. Salmon farming, it was thought, would follow the model of the local lobster industry: many small, independent operators, each with a vested interest in maintaining a sustainable sector.

“But it didn’t turn out like that, did it?” Wildish says. “I don’t think they realized it would be industrialized to the extent it has, and that big companies would take it over. And, of course, big companies want big profits.”

The results of that corporate approach were most obviously revealed to Wildish in Lime Kiln Bay. His specialty is the study of benthic conditions—the state of life on the ocean floor. Under salmon pens in Lime Kiln Bay, Wildish discovered virtual dead zones. The natural benthic environment was “destroyed.”

Those conditions were largely localized within the footprint of each pen, but there were also “bay-wide” environmental effects, he says. Organic material—from salmon feces to food waste—was suspended in the water across the bay. The brew snuffed out filter-feeding worms. Without worms to feed on, juvenile ground fish also disappeared.

The cause of the problem, Wildish says, was simple: overcrowding. Salmon pens were crammed into the bay with little regard for nature’s ability to process the by-products. In Dark Harbour, on Grand Manan Island, salmon died when oxygen levels dropped in the over-crowded waters. “Each cage site was like an experiment,” he says.

Wildish believes open-pen aquaculture can be run in an environmentally friendly way, and he argues the industry will be absolutely necessary after humans eventually haul the last wild fish from the ocean. But future aquaculture endeavours must avoid the mistakes made in New Brunswick, where Wildish says politics trumped science in establishing the industry. “You’ve got to do it in a way that is sensible. Otherwise you screw everything up,” he says. “I wish it could all start again.”

On the other side of the Bay of Fundy, the Nova Scotia government is pledging to avoid such pitfalls as it encourages amajor expansion of its salmon aquaculture industry. In May, the province unveiled an aquaculture strategy, aimed at alleviating environmental fears while creating rural “wealth.”

The strategy was announced at the Cedar Bay Grilling Company in Blandford, a hamlet on the province’s South Shore. The location was symbolic. Cedar Bay, which sells planked salmon, set up its operations in a shuttered salt fish plant. The company now employs 18 people as it ships frozen farm-grown salmon across North America.

“We were so dependent on our cod fisheries, but we do not have that option anymore,” said Sterling Belliveau, the province’s fisheries and aquaculture minister. “To me, the option is to grow fish and to make our coastal communities vibrant once again.”

Winning over skeptics, however, will clearly require more than the release of an industry-endorsed strategy that involved little public consultation.

Minutes after Belliveau finished speaking, a tense debate broke out between Bruce Hancock, executive director of the Aquaculture Association of Nova Scotia, and Raymond Plourde, Wilderness Coordinator with the Ecology Action Centre. Standing under a tent as a light rain fell, the two men exchanged terse arguments.

Hancock insisted his industry is committed to environmental monitoring and a “sustainable” number of fish per site. That pledge didn’t satisfy Plourde who, like many open-pen opponents, is calling for salmon to be raised in land-based (closed containment) tanks.

“As long as there is a free flow of biological interaction between the wild environment and the caged, industrial food fish… then we’re going to continue to have problems,” Plourde concluded.

In late June, with the lobster poisoning charges still lingering, the Nova Scotia government announced $25 million in loans and grants to aid Cooke’s expansion in the Bluenose province.

Back at Tangier Lobster, Stewart Lamont is looking over orders for the upcoming week, including a regular shipment of nearly 100 cases bound for Las Vegas.

Lamont agrees with Belliveau’s argument that many coastal communities are in need of revitalization; but he disagrees with the emphasis the fisheries and aquaculture minister is placing on open-pen salmon aquaculture as the remedy for rural decline.

“He’s trying to ride a pony to economic prosperity that’s not going to deliver. And, in fact, it places a lot of things we have in jeopardy,” says Lamont, a trained lawyer who sits on the board of the Lobster Council of Canada.

“Is this the model we want?”