There are times when we all crave the tried, fried and true.

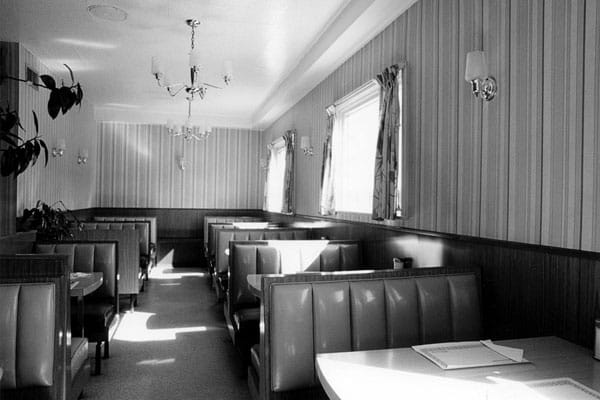

Slide into a vinyl booth at any classic East Coast diner and you'll be welcomed by a waitress who calls you "dear." There'll be a hot turkey sandwich, fries and rice pudding on the laminated menu, all freshly prepared in a kitchen or open grill where the food is not sautéed-it's sizzled. And although the placemat may be paper, the coffee will be strong.

The ubiquitous diner is a refuge from work, from the night before, from life. Most are cramped, noisy and egalitarian: business suits and political back-room boys sit booth-to-booth with truckers and the unemployed. The diner offers comfort food, and a comforting atmosphere. We linger there.

There is contention as to what constitutes a diner. Some aficionados insist only the sleek and shiny streetcar-shaped eateries found off highways and byways can wear the nametag. Others would argue, presumably over pudding, that cheap, stick-to-the-ribs fare enjoyed in a booth or at a counter is the defining criteria.

What true diners have in common-apart from the all-day homemade-style breakfasts and bottomless cups of coffee-is an unpretentious atmosphere where you can feel comfortable wearing, say, rubber boots. While Canada is home to a few flashy 1950s US-style diners, most establishments are humble roadside eateries or downtown, down-home, hole-in-the-wall finds-especially here in the Atlantic provinces. Diners may be as American as apple pie, but they are also as Canadian as maple syrup.

Diners may also reflect the neighbourhoods around them, absorbing the unique spicings of the owner's ethnic heritage, be it Greek, Chinese or Lebanese. These restaurants are ulticulturalism writ small, but writ with flavour. When all is said and eaten, the diner is an experience, not a structure.

Alas, the classic diner may seem as though it's always been there and always will be, but many are disappearing, smothered like gravy on french fries by fast food franchises. Since the 1970s, it's been getting more difficult to make cash from slinging hash. The greasy spoon is one of the last bastions of small, locally owned businesses being displaced by chains with head offices hundreds of miles away.

So if you find yourself in need of an affordable grease fix, forsake the prefab burger and check out a local diner. Following are a few classics to whet your appetite.

Nova Scotia

Halifax used to be home to such deliciously named establishments as the Tasty Foods Diner and the Bland Street Diner. They're gone, but you can still bite into a daily special at the Ardmore Tea Room (6499 Quinpool Rd). Established in 1958, the Ardmore is a landmark in Halifax, a place to go for hearty, inexpensive grub in a down-home setting. (In the aftermath of Hurricane Juan, rather than throw out soon-to-spoil food due to the power outage, Ardmore staff used gas burners to cook on the sidewalk for anyone needing a hot meal-just what you'd expect from a true diner.)

Another Halifax classic with a no-frills name is the South End Diner (1128 Barrington St), a small unassuming eatery with room only for counters and a kitchen-and some of the best daily specials in the city. For many years a corner store with an added soup and sandwich counter, it became a full-time greasy spoon in 1990.

Away from the sights, sounds and smells of the big city is the Turkeyburger, in Cookville, north of Bridgewater on Highway 10. An institution on the South Shore since 1954, this crowded eatery is a prototype of the Canadian roadside diner. Its specialty is, of course, turkey burgers and hot turkey sandwiches.

Prince Edward Island

Prince Edward Island is best known, culinary-wise, for lobster dinners. But if you still have room for a burger, you can drop by Charlottetown's Checker's Diner (41 University Ave), a 1950s-style family restaurant complete with a jukebox. Open seven days a week, it has all the usual fixings.

What's called a diner in Charlottetown is more often a lunch-bar; a convenience store with a counter and stools such as those found at Eddie's Lunch (35 Prince St). You can pick up milk, bread and eggs at Eddie's, or stay for the standard grill fare. There are also a few Lebanese dishes on the menu-shwarma, falafel, hummus-to keep things appetizingly interesting.

New Brunswick

Mel's Tearoom (17 Bridge St) is an institution in Sackville, and a regular haunt for students from Mount Allison University. Opened in 1919 by Mel Goodwin, the diner moved to its present location in 1944. Excellent home-style burgers, fries and shakes are accompanied by an original jukebox. Nothing contrived here.

Reggie's Diner in Saint John (26 Germain St) is another New Brunswick institution, around since the 1960s. With a relaxing, well lived-in ambience, this greasy spoon has the requisite dishes-all-day breakfast, burgers and shakes-plus excellent fish cakes and homemade baked beans.

Newfoundland

There are still a few fish left in the waters off Newfoundland, so any self-respecting restaurant in Canada's far east will serve a good feed of fish and chips. In fact, St. John's down-home culinary heritage may be sprinkled more with fish shops than diners, such as Avalon Fish & Chips (48 Kenmount Rd) or Ches's Fish & Chips (9 Freshwater Rd), which also makes its own vinegar.

But there are diner and family restaurants on the rock, such as The Big R (201 Blackmarsh Rd) in St. John's, CJ's Diner (21 Sagona Ave) in nearby Mount Pearl, and Debbie's Diner (McCurdy Dr) in Gander, in case you arrived by plane instead of ferry. Check the menu, as a solid diner in Newfoundland should offer a good "scoff," including the usual suspects of burgers, breakfasts and clubhouse sandwiches, along with traditional fare such as a "jiggs dinner"-potatoes, cabbage, salt meat, peas, carrots and turnips, all cooked in the same pot.

There's probably a diner nearby with great fries (or home fries or mash), juicy burgers, soggy open-face sandwiches and thick milkshakes. Squeeze into the squeaky comfort of a faded vinyl booth and ask about the specials. Enjoy the ambience, and don't forget the tip!

A short-order history

The history of what we call the North American diner begins in the late 1800s with horse-drawn lunch wagons, operated by men with names like Scotty, Gus and Joe. These roaming canteens pioneered the fast-food pick-up window-for five cents, late-shift factory workers were handed a hearty sandwich and a hot cup of coffee.

By the end of the century the wheels were off the lunch cart business after many cities, abuzz with electric trolley cars, banned the slower horse-powered wagons. Owners rolled their carts into vacant lots, covered the wheels, and re-opened as stationary snack shops. Old streetcars headed for the scrap heap were also converted into instant eateries by adding a grill. These transformed trolleys had room for a counter and stools, and customers could now eat inside. The modern-day diner was taking shape.

Entrepreneurs who could smell an opportunity started selling prefabricated lunch bars in the guise of trolley cars. "Ready to roll" straight from the factory, the canteens came with seats, a stove, pots and pans-even a kitchen sink. Soon restaurants modelled on the railway dining car jumped the tracks as well, and on city streets and highways across North America these dining cars became known as diners.

With the end of the Second World War, optimism was added to the menu, and manufacturers cooked up the future of diner design: glowing neon signs and curved stainless steel exteriors reflected the promise of post-war progress. In addition to counters, these larger prefabs had booths that could hold entire families-and formica tabletops that were easy to clean after they left. As the love affair with the automobile accelerated, hungry motorists were looking for places to stop and eat, and the 1950s and '60s would become the tastiest of times for the diner.

Some say that only these streamlined originals can be called diners, while others focus on the affordable, home-style food and unpretentious atmosphere regardless of the outside trappings. Today, both styles are called diners. But most Canadian diners, especially those here on the East Coast, are typically low-key, down-home establishments.

Sean Kelly lives in Prospect, NS. This story is adapted from a chapter on diners he contributed to The Food Lover's Guide to Canada published by Formac in October.