A look at Atlantic Canada’s first malt house, and the farmer who started it all

story and photography by Jodi DeLong

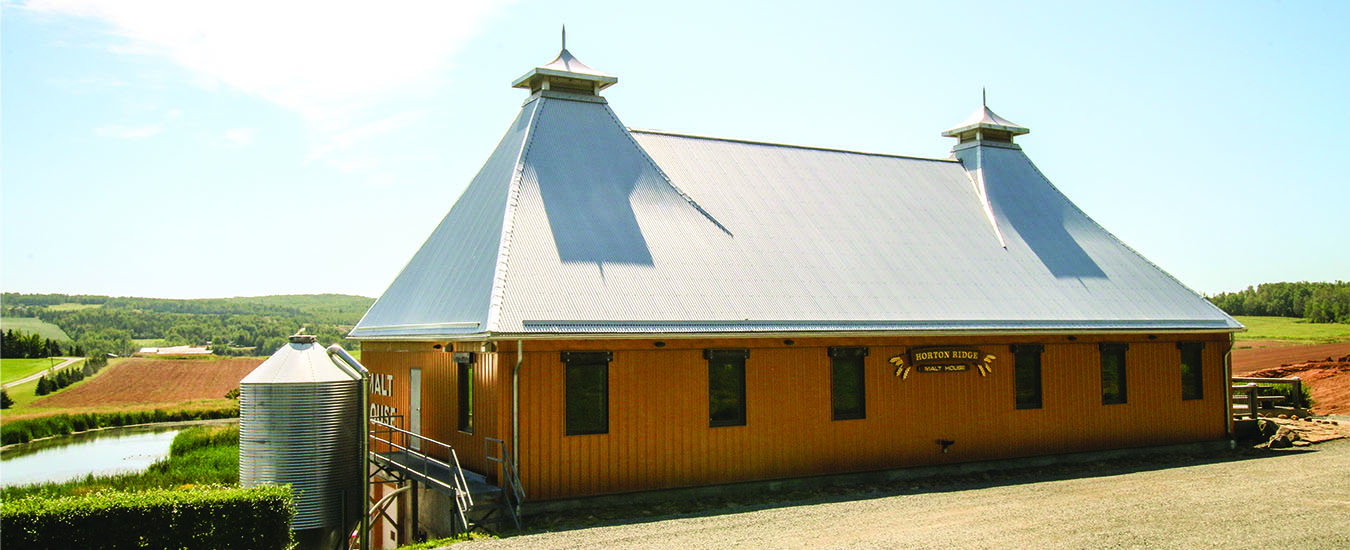

If you’re heading west on the 101 highway just before Grand-Pré, NS, you may have noticed a strikingly different building off to the south of the highway. Its high roofline is silvery white steel, crowned at either end with cupola-like structures, and the building itself is sheathed in a rich brown steel echoing the colours of the farmland around it.

Or perhaps, the colour of a good malt ale.

This is Horton Ridge Malt and Grain Company, the brainchild of sixth-generation farmer Alan Stewart, who can also lay claim to being the operator of the oldest registered organic farm in the province. Located in Hortonville, a tiny community adjoining Grand Pré, the malt house is the first such facility in all Atlantic Canada. For craft beer enthusiasts, it’s a boon to their production and to Alan, it’s also a way to connect another beverage we enjoy to its local agricultural roots in the Annapolis Valley.

Although trained as an engineer, Alan realized before he even completed his degrees that he wanted to return to the farm. His father had a small farm in the ill-fated Nova Scotian hog sector and struggled to make a living, as did many small farmers in the mid to late 20th century. Alan raised beef and grew organic vegetables, but it was often a challenging endeavour and he was looking for a way to make a decent income while also providing a needed product. The craft beer industry in Nova Scotia was exploding at the time, and, as he says, “Grain is used to make beer, and what a happy serendipity that is, because we can grow grain here, and we have a brewing industry that will buy it.” He did some research, and realized that you can’t use grain in its harvested form to make beer—it has to be malted first.

“I had no idea what malting was,” he admits with a chuckle, adding, “but I quickly learned, and I saw that it was the missing link between farming and brewing. So I decided to become the malt house.”

All about the barley

So, what is malt? Next to water, it’s the largest ingredient used in making beer, and is simply germinated grains such as barley, wheat, rye, and oats.

When a non-aficionado thinks about the makings of beer, they think of the grain, (usually barley) and of hops, yeast, water and perhaps other ingredients to make unusual flavours. They may not realize that the grain has to be encouraged to sprout first before it can make its magic in their favourite brew.

Alan explains, “Malting is germination and thus is very connected to farming through the nature of the process. A grain is a seed, and it has only one job—and that’s to reproduce. It’s not automatically made for flour or corn flakes or beer, it’s to make more grain. So when a grain goes into the ground at the right temperature and moisture, it will germinate.” During that process, enzymes in the seed start breaking down the starches into smaller starches and then sugars; the sugary bits are water soluble and go to the germ to give it the energy it needs to grow roots and a new plant. He adds, “Humans will make alcohol out of anything with sugar, so when we discovered we could turn grain from a starch to a sugar, and add yeast and hops and ferment the mixture, beer was born.”

Construction of the Horton Ridge malt house—which in its design pays tribute to the traditional malting kilns used in breweries and distilleries in Scotland—began in 2015, and by the following year Alan was making malt, but not from his own or other local barley. There are two distinctly different types of barley, two-row and six-row barley, which refers to the rows of seed in each head of grain. Two-row is most desirous for craft brewing.

There hasn’t been a lot of two-row barley grown in our region for several reasons. A drive around the Valley shows that there are fewer fields of small grains—barley, wheat, rye, oats—than there used to be, but there are ever-increasing fields of corn and soybeans taking up that acreage. Six-row barley grown here is primarily for livestock feed; it gives more yield but the kernels in a head aren’t uniform and are smaller in size than that in two-row barley. Alan says there are now some acres of two-row barley cultivated here, and he’s cautiously hopeful there will be a resurgence in small-grain growing as the desire for really-local brews is demanded by beer enthusiasts. The majority of organic barley they use now comes from western Canada or from PEI—where there is a good percentage of organic grain being grown.

“One third of what we malt here is currently wheat, rye and oats, and those are easy to grow so I focus on raising them,” Alan says.

Why is barley the preferred grain for beer? Simply put, the seeds are covered in a husk, which has no nutritional value, but when the sugary liquid is drained away from being in contact with the malt in the mash process, it drains through the husks which fall to the bottom of the tank, which makes the draining process much easier. Naked grains like wheat and rye create a more gelatinous liquid which doesn’t drain as nicely. Most beers are 80 to 100 per cent barley.

“We wanted to make beers

where you could actually taste the malt...”

The malting process

The first step in making malt is called steeping, where Alan and his team—son Connor, 27, is the malster, and Stephen Mastroianni is the brewer—add a tonne of grain to a big tank of water for up to 12 hours, depending on the grain. They drain the water away and let the grain sit and aerate for up to 10 hours, then repeat the process. After several days, a little white point sticks out of the grain—this is called the chit, the beginning of the seed’s rootlet.

Here’s where they do things traditionally. At most malt houses, grain is moved into large containers to continue the germination but at Horton Ridge, the grain is moved to the malt floor—a large, cool room with a concrete floor—and spread out to continue the germination process. The malt is raked every couple of hours to disperse the heat from germination, and to oxygenate the malt bed, Alan explains, “We want to see the creation of rootlets, and then before they start using the sugars in the seed, we stop the process by adding the malt to a simple hot kiln and drying it down.”

Before kilning, the germinated seeds are referred to as green malt, which can be used to produce a unique-tasting beer without going through the kilning process. Alan points out that using green, unkilned malt also makes it green in that it requires less energy to create it. Kilning can be done at various temperatures, which affect the malt’s colour and thus the colour of the beer—pale malt is kilned very lightly to make a pale ale, for example. Once kilning is complete the malt is bagged and sold to brewers as well as being used at Horton Ridge’s own beer-making facility. Since commencing operations in 2016, the malt house has produced about 100 metric tonnes a year—more than 350 batches so far—and each batch makes enough for 4,000 bottles of beer.

Photo Credit: Jodi DeLong

Truly local, truly craft

It was very important to Alan that his malt house be the conduit between local agriculture and local brewing. He points out that the grape growing and wine industry in Nova Scotia has a very good and visible connection between agriculture and winemaking—you can see the vineyards and taste the wines and get to know more about the importance to local economies. Craft brewing was devoid of that actual connection before Horton Ridge opened—people of course visit the many fine local breweries and sample the wares, but there was no focus in the industry about the most important ingredient in those brews—the grains.

Since Horton Ridge opened its doors, people flock to the facility to learn about malt, to sample the various beers made there as well as other locally-made offerings. Much of the malt that Alan sells is to two well-known Nova Scotian organic brewers—Big Spruce in Cape Breton, and Tatamagouche Brewing Company in Tatamagouche—and he always has a couple of offerings on tap from other local breweries who use his malts. He acknowledges that his malt is significantly more expensive than that sold by big commercial malt houses, but there is obviously a demand for it, particularly from organic brewers, who formerly had to get organic malt from Europe and western USA. Being able to get it locally is a real boon to brewers who pride themselves on their made-right-here products, and the benefits to the local economy are obvious in the busy, thriving breweries in towns around not just Nova Scotia but the region.

Of the beers produced on site, Alan says, “We wanted to make beers where you could actually taste the malt, so we laid off the hops to allow the flavour of the malt to shine through. That’s not been in vogue with most craft breweries, so we’re hoping to start a new trend for beer lovers.” This initially was a challenge for the brew team, but with some fine tuning they’ve created beers that are refreshing and flavourful and a little different from much of what is offered locally.

Craft beer accounts for maybe 10 per cent of the beer consumed in Nova Scotia, so part of the targeted customer base is the other 90 per cent who drink commercial beers and don’t always care for the hoppy brews offered from local establishments. This is the same sort of challenge that the local wine industry has had, and they’ve turned the challenge to their advantage, so Alan believes that craft brewers can do that as well.

With Horton Ridge well established and creating a name for itself, Alan is stepping back from this end of the process, retaining his role as president of the company, and returning to more grain growing, which is well suited to his acreage nearby. His daughter Emily, 28, works part time as a bartender and handles the social media for the operation, helping to spread the word about what they do at the malt house plus promoting their beers and items like hats and tee shirts in the tap house. Alan says, “I’ve enjoyed the process of dreaming up the idea of the malt house and brewery, and seeing it run smoothly—now I’m going to be a gentleman farmer and return to my roots and raise grain.”

“Having a malt house is like having a barn full of animals. The malt is alive and it’s our job to keep it alive, so that means many trips to the malt house, even if it’s a Sunday or holiday. It’s just like going to milk the cows—someone is going to the malt house

to rake the malt.” He won’t miss that

particular task.