A 1936 trans-Atlantic flight thrust a remote tip of Cape Breton into the international spotlight

MARY PRICE was only four when a turquoise plane with silver wings buzzed by her home at the southeastern tip of Cape Breton Island—and flew into aviation history.

“To see a plane coming low at that time was quite a thing,” she recalls of that September afternoon in 1936. The plane’s engine was sputtering, and the local fishermen “knew it was in trouble.”

The plane had been in the air 21 hours, battling heavy rain and strong headwinds in a courageous attempt—a foolhardy one, some said—to fly across the Atlantic from England. The engine let out a final cough, the propeller froze and the pilot aimed for a patch of level ground near the rocky shoreline.

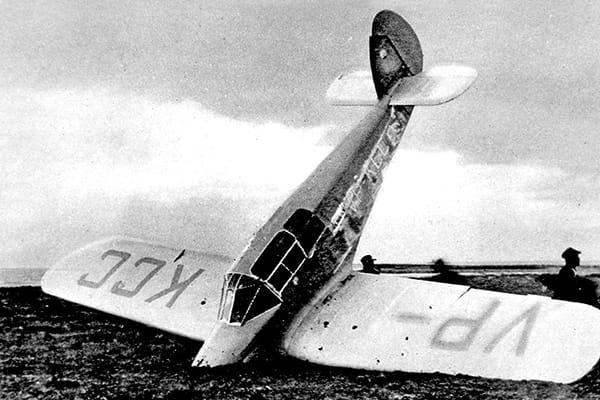

“The earth hurries to meet me,” the pilot would later write. “I bank, turn, and side-slip to dodge the boulders. My wheels touch, and I feel them submerge.” The plane lurched to a stop, its nose buried ostrich-like in the mud of a bog.

A tall figure with a mop of wavy blonde hair stumbled from the cockpit, bleeding from a cut where her forehead had struck the instrument panel. The pilot was Beryl Markham—the first person to make a non-stop solo flight from England to North America, and the first woman to fly alone across the Atlantic from east to west.

Flying “the hard way”

As the Spanish Civil War raged and Hitler prepared for war, Markham thrust her remote landing spot - Baleine, NS, population 20-something—into the international spotlight.

Born Beryl Clutterbuck in England in 1902, she had grown up in Kenya, where her father operated a ranch. She became a horse trainer and moved in the upper-crust circle depicted in the memoir-turned-movie Out of Africa, written by her Danish friend Karen Blixen under the pen name Isak Dinesen. Glamorous and blue-eyed, Markham was often compared to Greta Garbo. She carried herself with the elegance of an actress - one writer remarked on her “panther-like grace” - and was as comfortable in London’s high society as she was in the African bush.

She learned to fly in the early 1930s, ferrying supplies over the vast African countryside, spotting elephants and other big game for hunters. “Beryl never knew fear,” a friend noted. “She simply had no fear of anything.” By the time of her 1936 flight, she had gone through two husbands, had a young son and was notorious for having had an affair with Prince Henry, third son of George V.

The idea of crossing the Atlantic from England to America was hatched at a London dinner party. Charles Lindbergh and Amelia Earhart had soloed west to east but Markham would fly “the hard way” - westward, into opposing winds that made the flight much longer. A friend, aristocrat John Carberry, loaned her a plane that she christened The Messenger.

Markham prepared for the flight with Scottish aviator Jim Mollison, who had flown from Ireland to New Brunswick in 1932. She took off from an airfield near Oxford on September 4, despite a forecast of stormy weather. Mollison doubted her chances, telling an onlooker, “That’s the last we’ll see of Beryl.”

She flew in total darkness for most of the trip and almost crashed mid-ocean when the engine stalled as she switched to a fresh fuel tank. After skirting the Newfoundland coast at daybreak, the engine began to cut out—it was later determined that ice had choked off the fuel supply.

She diverted to the Sydney airport but could not maintain altitude. Fortified with two swigs from a brandy flask—“I suddenly felt much better,” she later joked—she picked a landing spot, and barely cleared the rooftops of Baleine’s cluster of houses.

The plane “dove straight down and zoomed up again, missing the telephone wire between my house and Fred Perry’s by about eight feet,” fisherman William Burke told the Halifax Herald. “Then she circled in the direction of the swamp.”

“Nice to have landed right side up”

Just up the coast in the village of Little Lorraine, Mary Price’s father and his neighbours saw the plane come down, and set out for Baleine on foot. She begged to go with them.

“Mary, you’re too young to walk and you’re too heavy to carry,” he said, “so you have to stay home.”

Burke - everyone called him Willie Vincent - was the first to reach Markham as she struggled out of knee-deep mud, looking nothing like a socialite with a scandalous past. They shook hands, he recalled years later, and the exhausted flier asked two questions: “Do you have a cigarette?” and “Where am I?”

Burke’s neighbour had a phone; Markham asked the operator in nearby Louisbourg to contact the Sydney airport, so no one would launch a search. The operator alerted Sydney doctor Freeman O’Neil, and merchant George Lewis, who drove to Baleine and brought Markham to his Louisbourg home.

She sipped a cup of tea as the doctor tended to the gash in her forehead. By a remarkable coincidence, Dr. O’Neil had patched up Jim Mollison after he’d crash-landed in a field near Sydney in 1932. Hearing this, “she sort of felt, ‘well, I’m among friends’,” says Harvey Lewis, George’s son. Markham borrowed a pair of Harvey’s father’s pyjamas and retired to their spare room to sleep.

“Within a few hours, the news people started to arrive,” says Lewis, who was 13 at the time. “My mother’s living room was a beehive of activity,” suddenly transformed into a radio station. At 8pm, Markham—sporting a large bandage on her forehead—was roused to describe her flight in one of Canada’s earliest live, nationwide radio broadcasts.

A syndication deal with Hearst Corporation restricted what she could say on air. “I’m feeling fine,” she assured the throng of frustrated reporters. “After all, it’s nice to have landed right side up on my first visit to America.”

After spending the night at the Lewis home, she was whisked to Sydney to catch a plane to New York. During a stopover in Halifax, Premier Angus L. Macdonald greeted her at Chebucto Field in the city’s west end. Surrounded by autograph seekers, she used the premier’s shoulder as a desk as she signed cigarette packs and scraps of paper.

A round of receptions and interviews awaited her in New York, where she apologized for not reaching her destination in her own plane. The next day, she vowed, would find her “indulging in the secret wish of every British woman - going shopping in New York.”

“It put Baleine on the map”

Back in Baleine, Mounties guarded The Messenger but souvenir hunters made off with the spark plugs and scraps of fabric before the plane was towed from the bog and sent by barge to Louisbourg for repairs. “It attracted an awful lot of people,” says Baleine fisherman Bill Burke, Willie Vincent’s second cousin. “It put Baleine on the map.”

Gary LeDrew, of Louisbourg, has a personal link to Markham’s flight. His parents, Harold LeDrew and Celia Shaw, were teenagers when Markham landed. “Everybody, of course, went from everywhere down to see it, and that’s where [my parents] met and started going together.” They married five years later.

Markham recounted her flight in West with the Night, an autobiography published in 1942. Ernest Hemingway described it to a friend as “a bloody wonderful book,” so well written that it made him “completely ashamed of myself as a writer.”

When Hemingway’s private endorsement was discovered, not long before Markham’s 1986 death in Kenya at 83, the book was reissued, becoming a bestseller.

Mary Price, who still lives in Little Lorraine, wishes her father had taken her with him that day to see the plane. A former costumed guide at Fortress of Louisbourg and life-long history buff, she was instrumental in having a plaque erected near the landing site in 1999, to record Markham’s achievement.

“What a great lady,” she says. “I admired her. I still do, to this day.”