How are our wildlife species holding up against an onslaught of habitat degradation?

In spite of its vastness and sparse human population, Canada has already lost 33 wildlife species to extinction, and more than 450 species are currently at risk. Recent additions to the list include sockeye and coho salmon in British Columbia and certain populations of Atlantic salmon in Atlantic Canada-species that only recently existed in high numbers but which have declined precipitously.

The vast majority of species at risk have been endangered due to loss and degradation of habitat. We commence, with this issue, a series by wildlife biologist Bob Bancroft, intended to take inventory of wildlife in Atlantic Canada. First, a two-part essay on mammals; later we move to birds and fish.

Snowshoe Hare (Lepus americanus)

Snowshoe hare habitat includes forests, thickets and swamps across Canada, the Rocky Mountains and the Arctic. Commonly called rabbits, they have brown fur in summer, replaced by a denser white coat every autumn. Large hind feet become furry "snowshoes" to help them hop atop deep snow and reach up to eat twigs and buds. Snowshoe hare populations fluctuate wildly: they will increase for years and then dramatically collapse. Reasons for this include-among other things-solar sun spot activity. With hare populations now very high in parts of the east, snowshoe hares can often be seen imitating lawn ornaments and lounging along country roads.

Current population status within Atlantic Canada: healthy

Moose (Alces alces)

Workhorse-sized moose are North America's largest member of the deer family. Found across forested regions of Canada except in Prince Edward Island, moose are well adapted to cold winters--less so to warming conditions. They are currently endangered on mainland Nova Scotia, but were imported to Cape Breton Island from Alberta in the 1940s to re-establish a population there. New Brunswick moose were successfully introduced to Newfoundland in 1904. Populations in Cape Breton and Newfoundland have been high for decades, and sometimes over-browse the forest. Young moose may grow five pounds (2.3 kg) a day. Factors influencing moose declines include a brainworm parasite carried by deer, fragmented habitat and access by poachers to wilderness strongholds.

Current population status within Atlantic Canada: Mainland Nova Scotia - threatened, Cape Breton, New Brunswick and Newfoundland & Labrador - healthy

Woodland Caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou)

Common throughout New Brunswick and Nova Scotia in the 1800s, caribou populations of this largest of the caribou strains collapsed there almost a century ago and are now in decline across Newfoundland, Labrador and westward over the north. Reasons for herd declines include global warming and related habitat changes, a docile, easy-to-hunt manner, and the recent thrust of forestry and gas pipeline activities into their habitats. Compounding these problems are two brainworm parasites, one accidentally introduced with reindeer (another caribou strain) from Europe to Newfoundland, and another that arrived with whitetail deer from the south. Newfoundland caribou populations also contend with a relatively new predator-the eastern coyote.

Current population status within Atlantic Canada: Labrador - healthy, Insular Newfoundland - vulnerable

Arctic Hare (Lepus arcticus)

Larger than snowshoe hares, Arctic hares weigh-on average-about eight pounds (3.6 kg). They feed on the tundra plants found on open ground in Newfoundland, coastal Labrador and across the far north. Arctic hares were once more common and inhabited forests in Newfoundland and coastal Labrador, but snowshoe hares, introduced there in 1864, soon displaced them from woodlands. Arctic hares hop up and down like kangaroos-on their hind legs with front paws up. Birds of prey and mammals like foxes and lynx often hunt this hare. With populations that fluctuate widely, they breed only once per year and average just three young per litter.

Current population status within Atlantic Canada: vulnerable

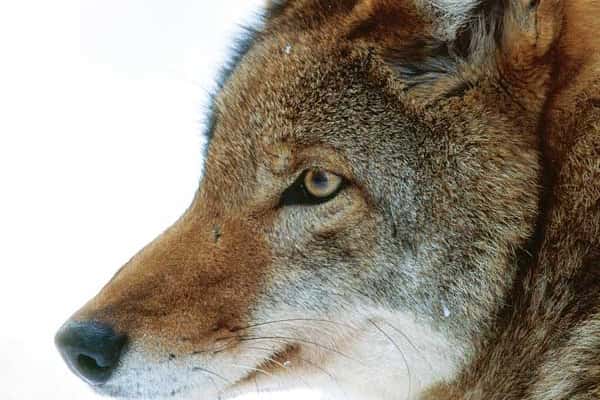

Eastern Coyote (Canis latrans)

Resembling wolves in size and sometimes travelling in packs, eastern coyotes appeared in New Brunswick in the late 1950s. They continued into Nova Scotia in the 1970s, eventually trotting across icy straits to Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland. Eastern coyotes are intelligent opportunists but fare poorly against northern wolves. Blueberries, bugs and a fawn may be on a day's menu, along with plundering garbage cans and village pets, but they more frequently travel forest roads, searching clearcut areas for mice and hares. Coyote populations occasionally contract mange, a painful condition that develops when mites invade fur, causing cracked skin and bare hides.

Current population status within Atlantic Canada: healthy

Bobcat (Lynx rufus)

Newfoundland and Prince Edward Island aside, bobcats roam across southern Canada. Opportunistic like the coyote, bobcats are capable of adapting to human encroachment. A bobcat or coyote might hide in the trunk of an abandoned '57 Buick, perhaps even within city limits. Bobcats normally haunt the swamps and forests of the east at night and alone, searching primarily for small mammals like squirrels, small birds and sometimes wandering domestic cats. Dens are often located in rock crevices, hollow logs and under wind-thrown trees. When fur prices rise, intense trapping of this easily caught species briefly lowers local populations.

Current population status within Atlantic Canada: healthy

(Nova Scotia has the highest bobcat population of any jurisdiction in North America.)

Red Fox (Vulpes fulva)

This small, wild dog with a bushy, white-tipped tail and a playful attitude prefers a mix of forest and open country. Although found across Canada, it avoids the prairies. The dens and middens (boneyards) of red fox pairs and their kits have long been associated with farmlands and orchards. Foxes will follow behind tractors as they mow hay fields, pouncing upon startled, suddenly exposed mice. Eastern coyotes with a penchant for killing foxes have pushed them closer to rural homesteads. Atlantic Canadian beaches often host fox dens in the sand dunes-they can be observed searching the beach grass for mice and birds.

Current population status within Atlantic Canada: healthy

Lynx (Lynx canadensis)

With tufted ears and enormous paws for easy treading over deep snow, lynx are larger and better equipped than bobcats for winters in forests and swamps across northern Canada. But wherever lynx and bobcat territories overlap, bobcats usually dominate. Lynx are absent in Prince Edward Island, and few currently remain on mainland Nova Scotia or New Brunswick. The Cape Breton lynx population is currently very low and considered isolated from other lynx populations across Canada. Lynx populations rise and fall in concert with fluctuations in hare populations. By nature a solitary, hide-and-pounce nocturnal hunter, the lynx is not well suited to prey upon other small wildlife species.

Current population status within Atlantic Canada: threatened